For the holidays, I'm driving across the US to visit relatives in both Atlanta and Cincinnati. Since I live in San Francisco, this entails a lot of driving. Thousands and thousands of miles worth in fact. And isn't this a fundamental part of who we are as Americans? I'm talking about one of the inalienable rights our founding fathers gave their lives for...the right to load up our cars with suitcases and bourbon, and drive across the endless landscape with our sunglasses on and the radio blaring.

Tonight I'm staying in Meridian, Mississippi, having crossed the great Mississippi River about 150 miles ago. And thus it's fitting that I'm currently reading Mark Twain's "Life on the Mississippi". This book, at least so far, is also about travel, about that American restlessness to move across the landscape. Twain was born in the river town of Hannibal, Missouri in 1835. At the time of his childhood this must have been a remote location indeed, except for the river. Near the book's beginning he tells of how the highlight of each day in his childhood Hannibal was when the riverboat came in. Otherwise the town was slow and sleepy. No wonder an intellectually gifted and curious child like himself grew up fascinated by the river. The same pull of adventure and the outside world that has lured countless of generations of young people also beckoned to Twain, and drew him to seek his adventures on the river. He fled Hannibal and apprenticed to become a steamboat pilot, and much of the rest of what I've read so far describes, humorously, his beginnings as a cub riverboat pilot. It's hard to tell what is the truth and what is exaggeration, as Twain describes how a pilot must know every bit of the river from St. Louis to New Orleans, lest he run his steamboat aground, or worse, especially when piloting at night when he can't see the way. Is this really true? I've had the same 35 mile commute each day for 12 years, and yet I'm not sure I could drive in the dark without headlights.

There is a wistful mood to this book. Clearly by the time he wrote it his river days were long past, and he describes how when he started to train as a riverboat pilot, the old days of rafts and flatboats on the river were long past, replaced by the steam boats. Thus in just the first 50 pages, Twain delves deep into two very American themes...the road trip (as mentioned above) and the nostalgia for a mythical American past. And perhaps the two really go together. For wasn't the movement of early Americans from the east coast out into the frontier really the ultimate American road trip? Yep, just like "On the Road", except the pioneers took all their worldly possessions with them and often died on their way, and didn't do nearly as many drugs. OK, maybe not. It's hard to tell after driving for 12 hours and then quaffing a couple of shots of bourbon. And I gotta hit the road again early tomorrow morning. It's the American way!

Sunday, December 21, 2008

Book #28 - Life on the Mississippi (Mark Twain)

Sunday, December 14, 2008

Book #27 - Lord of the Flies (William Golding)

Dark, darker, darkest. That seems to be my path by reading "Vanity Fair", "Pere Goriot", and "Lord of the Flies" all in a row. Because while Thackeray and Balzac have cynical, bleak views of humanity in their respective novels, Golding tops them all in "Lord of the Flies". The premise of his novel is that beneath a shallow layer of civilization lies a bloody pool of savagery in us all. Or as Margaret Thatcher once said "The veneer of civilization is very thin".

I remember seeing part of the movie version of this novel with my brother when I was very young, and it scared me to death. I had forgotten most of the movie, so it was fun to read the book. And I have to say the book is a real page turner. The story, which has really become a part of our cultural canon, is simple. A planeload of young boys is being evacuated from England because of war. It's not clear if this is World War II or some other fictitious war, although the "Reds" are mentioned at some point. Seems weird that children would be evacuated by plane to somewhere that they'd have to fly over the tropics to get to. Regardless, for some unmentioned reason, the plane crashes onto a deserted tropical island and the pilot(s) are killed. Only the boys are alive. Under the leadership of one of the older boys, Ralph, and advised by a smart but fat and sickly kid, Piggy, the boys form a rudimentary democracy. Ralph tells the boys they must build and maintain a signal fire, and they need to build shelter.

But things soon go awry. Another one of the boys, Jack, wants to be the leader. He takes up hunting, and leads a small group of boys who used to be his choir mates to become hunters of feral pigs found on the island. The kids quickly revert to savagery, in part driven on by their fear of "the beast", a monsterous creature they're convinced is out on the island somewhere. Jack and his hunters rebel and form their own tribe, and things quickly go downhill. Simon, a boy who is a saintly and wise, is killed in a ritualistic frenzy by the boys after they've eaten some freshly killed pig. He had come out of the jungle to tell the boys that what they thought was the beast was actually a dead parachutist. But he surprised the boys and they started to kill him with their spears, and even when they realized who he was they kept on stabbing him, due to their frenzy and blood-lust.

Piggy gets killed as well, buy a huge boulder pushed by Roger, the most sadistic of the kids. Finally all the boys on the island are in Jack's tribe except Ralph, and the kids start hunting for Ralph to finish him off. They set fire to the jungle to smoke him out, and so he runs to the beach, where he finds that British soldiers with machine guns have landed because they saw the huge jungle fire. Ralph tells them what's happened and the head solider says "But you kids are British, we expect better from you". Ralph cries with sadness and relief, and the boys are rescued. The End.

As I said, this was a great read, even with that deus ex machina ending. The language is taught and tense, and as the situation spirals downhill I really wanted to keep turning the page to see what happens. But I have to say, this book is not as complicated as the past few I've read. There is a lot of symbolism, but it's all pretty obvious...the pig's head (The Lord of the Flies) represents the beast within us all, Piggy's glasses represent knowledge and rationality, the conch represents the order, etc. And the main characters...Ralph, Roger, Jack, Simon, Piggy...all stand for specific types. Piggy is the intellectual, Ralph is the good, practical politician, Jack is the power hungry dictator, etc. It's a well written book, and fun to read, but maybe best read in high school, because the symbolism and allegory and characterization are all pretty black and white. But I don't mean for that to come off as an insult.

Still, the overall theme of this book is fascinating to think about. What WOULD happen in this situation? Are we really all just savages underneath? How dark is human nature? I can certainly see how Golding would have a dark view of the human psyche just after World War II when this was written. And in this age of terrorism the darkness continues. But nevertheless, society survives, as does civilization. We have laws, which are usually obeyed. Life on Earth is not the war of all against all of Thomas Hobbes. I can't argue that there isn't darkness in the human soul, but there's light in there as well, which has, over the centuries, triumphed over the darkness more often than the reverse. At least in the long run. So maybe Golding is a bit bleaker than is warranted. But ask me whether I still feel that way after the nuclear holocaust.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Blogging the Canon - Year One

Happy anniversary...to me! Yes, it's hard to believe, but it's been one year since I first started this blogging project! Woohoo, break out the absinthe! Actually, I'm sipping on some now, prepared in the traditional manner with sugar and water. I picked up a bottle when I was in London last spring, at the duty-free shop in Heathrow. It's pretty good...tastes like licorice, and has evil green color. And fortunately it hasn't driven me mad...yet. Ha, ha...wait, why are the walls moving?

This blogging project has been a great ride so far...26 books read in the year, out of my original 105, plus 76 blog posts, and countless cocktails while reading and blogging. So does that mean I'll finish up in three more years? Well, no, for two reasons. First, there are some remaining "books" on the list that are going to be incredibly long...like all of Plutarch's "Lives", and all of Proust's "In Search of Lost Time", which is actually something like a series of 18 novels or so. Second, during this past year, I've come across more books that should have been on the original "greatest hits of all time but have yet to read" list. In fact, I have 126 of these books. So why not add them to the list then, you may ask? Well, my fear is that I'll keep adding books in order to avoid some of the ones on my original 105 that I'm rather dreading, like "Ulysses" and "The Ambassadors". No, I think at least for now I'll keep plugging away at the original 105 books on my list, and hold off on the others for awhile.

It's fun to look back on the year and think of the books I've read. My favorite so far? Hmm, hard to say, but I think it might be...drum roll, please...George Eliot's "Silas Marner". I dunno, I guess I'm just a sentimentalist, but that book made me cry. Although parts of "Anna Karenina" and "My Antonia" made me cry too. My second favorite may have been "Moll Flanders"...that book is seriously funny! My least favorite? Hard to say, because I really liked them all. In fact, that's one of the surprising things to me...I liked them all! No clunkers out of the first 26! But I haven't read any Henry James yet, either.

I was thinking in my last blog post of common themes in several of the books I've read so far. The character of Moll Flanders reminded me a bit of Becky Sharp...both were intelligent, street-smart women who used their wiles to work their way up from poverty. But they were different, too. Moll was more of a good woman who did what she had to do to survive. Becky also did what she had to do to survive, but she definitely had a mean streak that Moll didn't have, and she aimed higher than just surviving. And Moll may have become an inveterate thief, but she would never have cheated on any of her men.

And then there's the similarities between Becky Sharp, Rastignac from "Pere Goriot", and Julien Sorel from "The Red and the Black". All three are intelligent, ambitious characters who escape from their impoverished, lower class beginnings by using their intelligence and cunning to move up the social ladder. Rastignac and Julien don't really know what they're doing, at least at first, but their ambition and drive allow them to overcome their naivity...at least for awhile (in Julien's case). We sympathize with all three, but all three definitely have their faults. But what's really fascinating is to compare these three characters to the lives of the authors of the three autobiographies I read this year: Benjamin Franklin, Frederick Douglass, and Booker T. Washington. All three of these men were also born impoverished and lower class...and in the case of Frederick Douglass and Booker Washington they were born slaves, which is pretty much as low in society as you can be. Like Becky and Rastignac and Julien, all three of the real life characters used their natural intelligence and incredible drive to escape from poverty and move up in the world. But where Becky and Rastignac and Julien used sex and trickery to move up the ladder, Franklin, Douglass, and Washington used hard work, and when that failed, more hard work. And when they reached the top, they worked to improve the lives of their fellow citizens, rather than simply kicking back and enjoying the comforts of high society. Does this reflect the difference between fiction and real life? Or does it just mean that real life Becky Sharps would not write an autobiography? Or does it mean that people who write their own autobiographies can leave out all traces of their duplicitous, cunning natures? The latter seems the least likely, since other historical sources would have revealed the truth if Benjamin Franklin or Booker T. Washington had slept their ways to the top. Hmm, well, let me sip my absinthe and ponder this mystery, as I pick up book #27 and begin my second year of blogging the canon.

Monday, December 8, 2008

Book #26 - Pere Goriot (Honore de Balzac)

Amateur Reader over at Wuthering Expectations recently celebrated a Big Balzac Blowout. This got me interested in checking the Frenchman out, so when I finished "Vanity Fair" I immediately dove into the one Balzac novel on my list, "Pere Goriot". And after reading "Vanity Fair" and "Pere Goriot" back-to-back, I immediately asked the question "Who has the more cynical and bleak view of human nature, Thackeray or Balzac?" Answer: yes.

"Pere Goriot" takes place in Paris, during the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, following the fall of Napoleon (coincidentally the same time period in which "Vanity Fair" takes place). The novel opens up at a rundown boarding house in Paris. Among the boarders is an impoverished old man named Goriot. As the novel opens, the other boarders single him out to be picked on for no real reason except he's old and quiet and shabby. They call him Pere Goriot, "Pere", of course, meaning "father" in French (Yes! I FINALLY can make use of that two years of high school French I took three decades ago! I knew it would eventually pay off!). It is rumored Pere Goriot was once a wealthy macaroni manufacturer, but no one really knows. That is, until he is befriended by another boarder, Eugene de Rastignac. Rastignac is a law student who is, shall we say, not the most motivated of law students. He pays a call on a rich but distant cousin of his who lives in Paris, Madame de Beauséant, and that's that. After seeing how the rich live, that's all he wants...to be filthy, stinking rich, and to pal around with other rich aristocrats. Oh, and without studying this boring law stuff. He soon learns that Goriot has two daughters who are rich Parisians, having married wealthy men. He visits them to try to make inroads into Parisian society. Balzac's descriptions of Rastignac's initial visits to his wealthy cousin and to one of Goriot's daughters, the countess Anastasie de Restaud, are both very comical and quite painful to read. Rastignac is from the south of France, and seems to be what we might call today a "country bumpkin", or a "hick". He doesn't know the rules of society and totally puts his foot in his mouth, among other things. But he's determined to learn the rules of aristocratic society, and slowly becomes more adept at the game. Eventually he becomes the lover of Goriot's other daughter, Delphine de Nuncigen.

Meanwhile, we learn more about Pere Goriot. He was indeed once a wealthy macaroni manufacturer, but he has given all his money to his daughters, first as a dowry, and later to help pay debts incurred by their lovers. In fact, Goriot is obsessed by his daughters...all he can talk about is how much he loves them, and how he'd do anything to help them, including, as it turns out, selling all he has and going broke for them. And how do the daughters feel about him? They take his money and never visit. Kids today, I tell you.

In a twist, which never really goes as far as the reader thinks it will, there's another boarder at the house, Vautrin, who befriends Rastignac. It's pretty clear there's something going on with Vautrin, because his character seems quite sinister, although for awhile it's unclear why. Vautrin tries to convince Rastignac that if it's riches he wants, he should court another woman that lives at the boarding house, Victorine Taillefer. Victorine is a daughter of a rich man who has disinherited Victorine and her mother. Vautrin tells Rastignac to court Victorine, and meanwhile he will arrange for her father's son and only heir to meet with an unfortunate accident, which will cause the father to make amends with Victorine since he has no other heirs. Rastignac actually toys with this idea, briefly, and flirts with Victorine, but then goes back to Goriot's daughter. To make a long story short, Vautrin has the son killed anyway (oops) but Rastignac doesn't go along and the Vautrin is exposed as some kind of master criminal who the cops have been after for years. He's arrested and hauled off by the police. Melodramatic? Yeah, you think? Balzac is great with descriptions, sometimes going off on the smallest details, but he pulls it off because it's always interesting. But his plot twists can be pretty melodramatic, and sometimes a bit over the top.

Anyway, I won't go into all the details, but Rastignac works it so that Delphine gets him his own furnished apartment so she can have access to him whenever she wants. But soon Goriot, who it turns out is paying for the apartment (of course) because that's what his daughter wants, becomes ill, and appears to have a stroke or something, brought on because his other daughter, Anastasie, is in trouble since she had to pawn her husband's family diamonds to pay off the gambling debts of her lover. Goriot, finally tapped out, has a stroke because he is powerless help his daughter. On his deathbed, his daughters are called, but neither of them can come, due to, well, some lame excuses. Goriot finally realizes that maybe he's loved his daughters too much and that actually they are scumbags. Anastasie finally comes to his deathbed, but it's too late as he's already in a coma and fading fast. And so he dies. Only Rastignac and a medical student friend come to his burial. This whole experience has made Rastignac realize how shallow both the daughters and Parisian high society are. For a brief instant the reader thinks that maybe Rastignac will reform his goldigger gigilo ways...but no. After Goriot is buried, Rastignac faces the Parisian skyline from a hilltop in the cemetary and says something like "It's between you and me now!", or "Henceforth there is war between us", depending on the translation. Then he goes and dines with Delphine, who's just blown off her father's burial. The end. So although he's given in to temptation, it's an adversarial relationship between him and the society on which he is looking to build his ambitions.

Cynical? You bet! It's fun to compare this book to "Vanity Fair" in that way. Both have dark views of human motivations and behavior. It's also interesting to compare this story to "The Red and the Black". The writing styles of Balzac and Stendhal couldn't be more different, but the stories are both about ambitious, poor young men who use their charms with the ladies to (1) get laid and (2) move up in society to gain status and riches. Sigh...if only I had thought of that plan myself 25 or 30 years ago. But no, instead I had to go to grad school.

Anyway, this was a fun, quick read, and Balzac is a great writer with, as I said, a flair for description. I'd like to read more of him eventually. Apparently most of the characters in "Pere Goriot" recur in other parts of Balzac's works. It would be fun to revisit them. And who knows...maybe they get nicer, more generous, and more unselfish in their old age. Nah, just kidding.

Thursday, November 27, 2008

Vanity Fair's Conclusion (Spoiler Alert!), plus More Alcohol!

I finished "Vanity Fair" today, and to celebrate I'm drinking a glass of rack punch, the drink that did in Joseph Sedley. More on this rack punch in a bit. But first, then end of "Vanity Fair"!

To start, I have to say that Thackeray is one hell of a writer. I just needed make that clear. There's a lot going on at the book's end and I'll just comment on a few things. First, old Dobbin finally grows a pair! Trying to warn Amelia of Becky's nature, Amelia gets pissed at him, and he says, basically, "I'm over it" and leaves Amelia. He gives up on the woman he's been trying to woo for years, realizing that it's hopeless and he's just wasting his time. And so what happens? Of course, Amelia starts realizing how great he's been to her. Yep, it's the old "they want what they can't have", also known as "playing hard to get". As soon as Dobbin tells her off and leaves, Amelia now wants him. Funny how that works. So finally Amelia writes Dobbin and tells him to come back and marry her. And at the same time, Becky actually shows some real emotion and tells Amelia that Dobbin is a great guy and she should go after him, and by the way, her (Amelia's) husband had wanted to run away with Becky and here's the note he wrote to her that proves it and maybe Amelia shouldn't be idolizing him so. Oooh, snap! So Dobbin returns, and Amelia is grateful and they get married and have a daughter and live happily ever after. Well, except Thackeray throws this little tidbit in:

Good-bye, Colonel - God bless you, honest William! - Farewell, dear Amelia - Grow green again, tender little parasite, round the rugged old oak to which you cling!

Parasite!?! OUCH! And yet, it's so true. Dobbin got what he always wanted, and maybe that's not so great. "Which of us has his desire? or, having it, is satisfied?" God, I love this book.

And then there's Becky. Oh, Becky. I touched upon previously the question of whether she was guilty of not in having an affair with Lord Steyne. While this is an open question, she seems to get more and more evil as the book ends. Or at least, it's implied that she's evil, although again it's mostly hearsay. But something very curious happens at the end of the novel. Becky has taken up with old Joseph Sedley, not in a sexual way, but she has worked the situation so that Sedley is supporting her. Dobbin comes to Sedley's room and tells him he should just leave and not tell Becky, and Joseph says:

He would go back to India. He would do anything; only he must have time: they musn't say anything to Mrs. Crawley: - she'd - she'd kill me if she knew it. You don't know what a terrible woman she is.

Now here's the interesting part: Becky is not in the room, nor is she eavesdropping, when Joseph says all this to Dobbin. At least, that's not mentioned in the text. But Thackeray has an illustration called "Becky's second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra" where she's apparently hiding behind a curtain listening in to this conversation. And several months later Joseph Sedley is dead, and hey, that's a coincidence, Becky gets half the money from his life insurance. So are we to assume Becky killed Joseph? Clytemnestra, for those of you who might not remember their Greek mythology so well, was the wife of Agamenon who murdered him after he returned from the Trojan War. The illustrations (drawn by Thackeray himself) have so far been just illustrations of the scenes in the novel, and yet this one differs from the text. What are we to make of that?

And another curious thing, which, in order to really understand, I'd have to reread the novel, paying close attention to this, is the narrator. I find the narrator of this book quite fascinating. At the novel's beginning, Thackeray talks about being a puppet master, and makes his narrator seem like the all knowing guy who made this shit up. Yet, as the novel moves along, the narrator's voice changes, or maybe just becomes more complex. There are times when the narrator says he doesn't know what happens either inside someone's head, or behind closed doors (and damn it, I didn't write these instances down, so I can't cite them here). And then there's this passage, in Chapter 62, where Dobbin, Amelia, Sedley, and Georgey all go traveling to Germany, and to the town of Pumpernickle. The narrator states:

It was on this very tour that I, the present writer of a history of which every word is true, had the pleasure to see them first, and to make their acquaintance.

Huh? If the narrator is the omniscient puppet master, how can he just make their acquaintance in an obscure German town? And how can he say every word is true when he's belied that before? I dunno. Maybe he's speaking in more metaphysical terms. Maybe "every word is true" means that his picture of humanity is all true. Or something like that. Or not. My powers of analysis fail me here. Or maybe that's just the rack punch kicking in.

And speaking of rack punch, in honor of this awesome novel I have recreated the drink that kicked Joseph Sedley's ass. First, as I previously posted rack punch refers to Arrack punch, and a recipe for that can be found here. This recipe is from the classic cocktail book "How to Mix Drinks" by Jerry Thomas, written in 1862. It's basically the original bartender's guide. Since it's written just 14 years after "Vanity Fair", we can hopefully assume that the rack punch recipe in the book is the same as the one Thackeray had in mind. Anyway, to make this drink, I first had to find some Arrack. Fortunately, arrack is still available, although hard to find, and I managed to procure a bottle from my local BevMo. The arrack I bought, called Batavia-Arrack, is distilled from sugar cane (98%) and Java red rice (2%). It was distilled in Java, blended in Amsterdam (Java was the Dutch East Indies), and produced in Austria (not sure what "produced" means). It's 50% alcohol (100 proof). I tasted some neat, and it tastes very similar to rum, which you might expect since rum is generally distilled from sugar cane, but there's a definite non-rum taste in there as well, presumably from the rice. The rack punch recipe calls for mixing the Arrack with rum, lemon juice, simple syrup, and water, which I did. I shook the punch in a shaker with ice, and poured into a cocktail glass. The results are shown here:

The verdict: not bad. In fact, I can see how Joseph might have enjoyed a full bowl of this. It's lemony, and sweet but not too sweet, and you can definitely taste the rum and Arrack. But since it's cut with water, it's only about 20% alcohol, so it's pretty smooth and could be drunk at a quick pace. And it packs, no pun intended, a punch. Mmmmm.

One more alcohol obscurity pops up towards the end of "Vanity Fair". When the characters are in the town of Pumpernickle, they and the townspeople are noted at several points to be drinking "small beer". Fortunately, because I am living in San Francisco, I not only know what small beer is, but I have tasted it as well. Small beer is an English invention, dating from the 1700s. When a brewer made a batch of a strongly-flavored beer, they would use lots of malt, hops, and grains. After the beer was made, they would pour off the new batch of beer, and then add more water and yeast to the wort, or grain residue, and then brew a second batch of beer without adding new grain. Because the first batch of beer used up much of the flavorings and sugars in the grain, this second batch, called small beer, would be a more mildly-flavored beer, and would have less alcohol, since there was now less sugar for the yeast to ferment. There is only one small beer I know of that is still made today, and it's produced by the Anchor Brewery in San Francisco. I've only ever seen the beer sold here in San Francisco, but I have had it a few times, and I love it. Anchor Small Beer is very light, and also very bitter, but bitter in that great beer way. It reminds me of a bitter cask ale that one might find on tap in an English pub. Definitely worth seeking out and picking up a bottle or two. And in case you haven't figured it out by now, "Vanity Fair" is definitely worth picking up as well.

Monday, November 24, 2008

A Fair Fight

Unbelievably, I am nearing the end of "Vanity Fair"! Just about 70 pages to go, so I should finish it this week. Oh yeah! I'm still enjoying it, but also still having a hard time trying to fit reading into my recent schedule. Ah well. Here are a few of the thoughts I've had while reading the last 100 pages or so:

1. There's a pivotal moment in the plot when Rawdon finds his wife Becky with Lord Steyne. Steyne has carefully gotten rid of everyone around Becky...shipping her son off to a good school, and getting rid of her housekeeper. He then arranges to have Rawdon detained in jail over his debts. Rawdon manages to get out, and comes home to find Becky alone with Lord Steyne. And then...The Smackdown!! Rawdon gives Lord Steyne a taste of his fist, knocking him down, leaving a scar, and acting all manly. And what's Becky's reaction...she's into it! She gets all hot over Rawdon, who she's been scorning for the last 200 pages. Unfortunately he leaves her, because he suspects, with good reason, that she's been going at it with Lord Steyne. But it's weird, her reaction. I guess she likes a good show of testosterone.

2. And another thing about that pivotal moment...was Becky really getting it on with Lord Steyne? Were they having sex or not? It's never clear. Naturally, we are inclined to think the worst of Becky. I said previously that I didn't think she was really evil, but her behavior was getting worse and worse. The other ambiguous thing was the final outcome of the Rawdon/Steyne conflagration. Rawdon is so angry at Steyne for putting the moves on his wife that he challenges him to a duel. Or at least he tries to, but is thwarted by a smooth talking second. And then Steyne makes Rawdon governor of some tropical colony. It's not clear to me if he planned this before The Smackdown or after. Either way, Rawdon ends up taking the position (which has a nice salary and perks) and seems mollifed by arguments suggesting Becky did not sleep with Steyne. Which seems kinda wimpy to me. Rawdon, after a ballsy show of manliness, ends up letting himself be bought out. Par for the course in "Vanity Fair", I suppose.

3. In reading "Vanity Fair" and reflecting back on "The Red and the Black", one realizes just what a big deal Napoleon was for Europe in the early 1800s. After World Wars I and II the Napoleonic wars can seem a little quaint. But they weren't.

4. I really want Amelia and Dobbin to get together. Even though Amelia is an idiot for pining her life away over George and for not appreciating Dobbin, and Dobbin really should have let go of Amelia a long time ago and moved on. But they better hurry...there's only 70 more pages to make it happen.

Sunday, November 16, 2008

Still Here!

I am a bad, bad book blogger. I mean, the whole point of this blog is to plow through the greatest literature EVER, with occasional sips of whiskey and a full report of my activities. But unfortunately, my life lately has been mostly work and little literature, albeit still with the occasional sips of whiskey. I'm now a little over 2/3 of the way through "Vanity Fair". Reading a book this slowly is not as great an experience as reading a book quickly. The continuity of the book gets a bit lost; when I pick up the book after not reading for a few days it can take me a few pages to remember what the heck is going on. And this is a long book, so it's getting stretched out even longer. Ah well. I'm hoping my current slow progress through the canon will pick up its pace in the coming weeks, but we'll see.

Anyway, enough self-pitying and whining! Let's talk f$&king literature! Here are a few random thoughts I'm having while continuing my way through "Vanity Fair":

1. What kind of a guy was Thackeray anyway, I wonder? Did people like hanging out with him? Was he ripped off by a bunch of grifters at an early age? I mean, from this book it's clear he's a brilliant writer, and a sharp observer of human nature, and he's got a wicked sense of humor, but he's also got a way cynical view of humankind. It reminds me of the line from an Elvis Costello song: "I used to be disgusted, but now I'm just amused".

2. Finally in Chapter 50, we had an incident that I would describe as poignant. Amelia and her beloved son are living at her parents' house. Actually it's not her parents' house because the parents, since her father's bankruptcy, are living in someone else's house as renters, although they can't make their rent payments since their father is continually losing money through failed business schemes. Amelia realizes her son is not going to get ahead in life by living in poverty. Her dead husband's wealthy father, who hates Amelia's father, has suggested that he should raise the son in order to give him an advantage in life. Amelia is initially repelled by this idea, because her son is all she has left in the world to love since her beloved husband's death. (The husband was kind of a dick, by the way, who never really appreciated her). But as finances get tighter and tighter, she finally decides she has to do what is best for the son, and she lets him go live with his paternal grandfather. This is very touching, because not only is she completely devastated over her sacrifice, but her little boy is pretty psyched about it. He goes away happily, and is looking forward to living as a rich person. The child still has some good nature...he gives away money to a poor begging child who the adults tried to shoo away...but he's also part greedy money-grubber, just like many of the adults in the book. Vanity Fair starts at a young age, I suppose. Perhaps it's even genetic. I'll look into that.

3. Are we supposed to hate Becky Sharp? She cracks me up. There are two full chapters dedicated to explaining how she and her husband can live on no income. You go girl! Currently she's hanging out with Lord Steyne, who is helping her climb the social rungs into the highest levels of society. Becky has her faults, to say the least...she's manipulative, cold, doesn't seem to care at all for her son...but you also have to admire her spunk, her social intelligence, her wits. Her climb in society depends a lot on her natural beauty and talents. She would do quite well in contemporary America, where the class of one's birth matters far less than in Victorian England. If she were alive today I could see her being a major player in Hollywood.

4. This is a great book, and fun to read, so I hate to complain...and maybe it's just me taking way too long to read this book...but there are times I think Thackeray seems to ramble a bit. Of course, it was a serialized novel, so maybe he was just padding it out to fill each installment.

5. Some of the characters in the book drink alcohol mixed with water, as in gin-and-water and rum-and-water. I can't quite figure that out. It reminds me of General Jack Ripper in "Dr. Strangelove" who would only drink grain alcohol and rainwater. Are the characters drinking alcohol diluted with tap water? Or is it carbonated water like club soda, or tonic water, both of which would seem like more tasty options, at least to the modern palate? And did they have ice in the household in England in the very early 1800s? Or were the drinks all at room temperature? I need to look into this.

Monday, November 3, 2008

A Fair Question

I hate it when I'm reading along in a book and I read a chapter and suddenly realize I have no idea what the f@#k is going on. This happened to me in chapter 29 of "Vanity Fair" entitled "Brussels". Our cast of characters, Becky and her husband Rawden Crawley, George and his wife Amelia, Captain Dobbin, and Amelia's brother Joseph all go to Belgium, since Napolean is back in France and it's clear a final battle will be coming. This in itself made me laugh...man, war has sure changed in the past 200 years. All the soldiers were responsible for shipping themselves to Belgium, and many took their wives and families, with other hangers on, like Joseph Sedley, just dressing up in any makeshift uniform they could find and going along just for the parties. And party they did...arriving at Belgium, everyone hangs out drinking and going to fancy balls until the orders to march come down.

But here's the part I didn't understand. The two couples, Rawden and Becky, and Joseph and Amelia, have been good friends. It's true, Rawden and Jopseph gamble together, which usually results in Rawden taking Joseph's money, but still. But then there's this scene at a ball in chapter 29 where Becky and Joseph flirt massively, and Amelia is ignored, except when Becky comes up to Amelia and totally rags all over her. I don't understand where this is coming from. Why is Becky doing this? Is it simple lust? Not likely, because Becky is too calculating for that. Why does Becky turn on her friend like this? There has to be an angle, but I didn't catch it while I was reading.

Nonetheless, this new behavior of Becky's is quite evil, more than we've seen so far, so I take away some of my more benign assessment of her that I proclaimed in my last post.

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Fairly Slow Going

The corner convenience store at the end of my block closed its doors today. Apparently the landlord wants to put in an art gallery or something, so the store where I buy my newspapers, saltines, and beer got the boot. Yesterday I saw a sign in their window that announced a closing sale with 50% off on all their remaining liquor stock. Naturally, that caught my eye. But when I went in and looked at the shelf, I saw that all they had left were a few bottles of blackberry brandy, butterscotch schnapps, and Hennessy. Not being able to resist a good deal, but not wanting to make myself sick either, I sprung for a bottle of the Hennessy. At 50% off of the usual corner store inflated prices, I figure I probably got the equivalent of a 10% discount off the regular price at any discount liquor store. Nonetheless, as I blog tonight, I'm in a mellow mood, sipping on some fine cognac. Of course, I know nothing at all about cognac, and I don't know if Hennessy is actually considered a fine one or not. I mean, the ads look convincing, and all the hip hop artists drink it, so it has to be pretty good, right? Back me up here, because I really have no idea.

"What's the point of all this rambling?", you may be asking. "Why doesn't he stop this blathering on about store closings and booze and get back to the discussion of "Vanity Fair". He's distracting us from the issue at hand!"

Well, that's correct, and that seems to be my problem at the moment. You see, I've been reading "Vanity Fair" for like what, a month now? And I'm only 250 pages into this 678 page book. Why is that? Well, partly because I've been busy scouring the neighborhood like a vulture looking for boozy bargains at businesses that are going belly up. But partly because I seem to find myself getting distracted when I read this book. I'll sit down to read, and get 2-3 pages into it, and then my mind begins to wander. The next thing I know I'm leaping up off the couch to check on the latest election polls, or to google the name of that song that's running through my head to see who wrote it. And I'm not sure why this is happening, although as a scientist I have several possible hypotheses: (1) I'm losing it, probably due to early onset Alzheimer's, (2) I've got a lot going on in my life, and finding it hard to focus at the moment so just GET OFF MY BACK DAMMIT, (3) the book is boring me silly, or (4) something else. Upon reflection, aided by the Hennessy VS, a cognac which may or may cause cognac connoisseurs everywhere to laugh when they hear that I'm drinking it, I have to say that none of these hypotheses seem accurate except for #4, "something else". I like the novel, and I don't find it boring...not at all, in fact. I think it's more that the language that the book is written in, and by that I mean the sentence structure and the vocabulary, as well as the subtlety and sophistication of the thought, makes this the type of writing that has to be read slowly, and rolled around on the tongue and enjoyed like a fine cognac, in order to be appreciated. This book needs to be savored as well as read, and that takes time. It also tends to make my mind wander, though that's my fault and not Thackeray's. Anyway, it's slow going.

And what about the story? Well, just a couple of notes. First, the humor has changed since the first few pages. It's become more subtle, and frankly more biting. I have to wonder if Thackeray really likes any of his characters. They're all conniving, or money-grubbing, or just silly and oblivious. The only one who's close to being a good and admirable character is Captain Dobbin, who's secretly in love with his best friend George's girl, and convinces George to marry her when he sees that the girl is pining away for him. So he's noble, but he's also somewhat of a milquetoast. I find it interesting to think about the contrast between Thackeray's characters in "Vanity Fair" and Dickens' characters in "Bleak House". Dickens certainly lampooned some of his characters, and made some of them almost cartoon-like, which Thackeray does not do...Thackeray's humor towards his characters has more bite to it...to say his humor is meaner is too strong, but it is more cutting...it feels to me like there's a hint of darkness to it. Also, in "Bleak House" you have a sentimentality that is lacking, at least so far, in "Vanity Fair" (I'm particularly thinking of Jo's death scene...I can't imagine Thackeray writing that).

Having said all that, none of the characters in "Vanity Fair" are really evil, or anything like that. They're just more like buffoons. Except Becky, who is very cunning. But I can't even say she is evil, because she's merely opportunistic. She's smart and attractive, and she knows it, so she goes about using what she has to better her lot in life. Seems fair to me. Anyway, I seem to be rambling and distracted, so I might as well go back to my reading.

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Whiskey Punch Update

Since nothing is more important to my enjoyment of classic literature than alcoholic accuracy, I decided to pursue the question of what might have been in that bowl of whiskey punch that Joseph Sedley drank, much to his disadvantage, in Chapter 6 ("Vauxhall") of "Vanity Fair". I contacted my friend and internationally known vintage cocktail expert Erik Ellestad. Mr. Ellestad got his start in the world of vintage cocktails by his continuing efforts to make every cocktail in the Savoy Cocktail Book, a classic and comprehensive cocktail recipe book published just after Prohibition. I contacted Erik and asked him what might have been in a whiskey punch made in England in 1847-1848 (the years "Vanity Fair" was published). He pointed me to this recipe which is basically whiskey (either Scotch or Irish), hot water, lemon peel, and sugar, with maybe a little nutmeg. Sounds pretty good to me. But alas, then I reread the passage in "Vanity Fair" and found that Thackeray describes the drink as "rack punch", rather than whiskey punch! Oops, was I drunk on punch when reading that passage?? Odd, I could have sworn I read "whiskey punch". Further inspection revealed that the reference to whiskey punch that I remembered was in Chapter 8, when Osborne and his men are singing songs in their barracks over a whiskey punch:

All things considered, I think it was as well the gates were shut, and the sentry allowed no one to pass; so that the poor little white-robed angel (Amelia) could not hear the songs those young fellows were roaring over the whiskey-punch.

Interesting. In the Vauxhall chapter, Joseph Sedley orders his rack punch, and Thackeray says that Osborne didn't like it. This seems like that the rack punch is then a different drink, as Osborne is clearly enjoying whiskey punch with his men two chapters alter. So what could "rack punch" be? With the help of google, I found this gem:

I must close with two familiar words which have been so long with us that few who use them ever suspect that they came from the East—namely, Punch and Toddy. The Rev. J. Ovington, who sailed to Bombay in 1689, in the ship that carried the glad news of the coronation of William and Mary, tells us that, in the East India Company's chief factory at Surat, the common table was supplied with "plenty of generous Sherash (Shiraz) wine and arak Punch," Arrack (properly "Urk"), sometimes abbreviated to Rack, means any distilled spirit, or essence, but is commonly used to distinguish country liquor from imported spirits. The Company's factors drank it because European wines and beer were at that time very expensive in India, and to reconcile it to their palates they made it into a brew called Punch, from the Indian word "panch," meaning five, because it contained five ingredients—viz. arrack, hot water, limes, sugar and spice. This was the ordinary drink of poor Englishmen in India for a longtime, and public "Punch-houses" existed in every settlement of the East India Company.

Now, one of the principal substances from which country liquor is distilled is palm juice, the native name for which, "tadee," has been perverted into "toddy" (as in the case of "cot" above-mentioned), and "toddy punch" meant the same thing as "arrack punch," Returning Anglo-Indians brought the receipt for making this brew to England, and lovers of Vanity Fair will remember how the whole course of that story was changed by the bowl of "rack punch" which Joseph Sedley ordered at Vauxhall, where "everybody had rack punch." How soon both the brew and its Indian name took firm root and spread among us appears from the fact that, at the Holy Fair described by Burns in the century before last, the lads and lasses sit round a table and "steer about the toddy."

Sounds like the same drink as whiskey punch, but made with Arrack (see here as well). Since Joseph had lived in India this makes total sense. I found these recipes for Arrack Punch, which are in line with the other punch recipes (booze, lemons, sugar, water) although the drink can include rum as well as the Arrack. But I think we at least have the gist of the drink that got Joseph Sedley so drunk, and then painfully hung over. But why didn't Osborne like it? Or was he just on his best behavior because of Amelia?

It's also interesting that Arrack can be made from palm juice, since Okonkwo and his tribe all drank palm wine in "Things Fall Apart".

Whew, that was some detective work. I think I need a drink now! One bowl of rack punch, please!

Monday, October 20, 2008

Book #25 - Vanity Fair (William Makepeace Thackeray)

I've been a bad, bad blogger. I haven't posted in two weeks. Did I finish "Vanity Fair"? Was I too convulsed on the floor with laughter to write up my thoughts? Or was I just too drunk on whiskey punch, like Joseph Sedley? No, I've merely been busy with work, and with travel for work. As a result, I've only read 140 pages of "Vanity Fair", out of 688 pages in the edition I'm reading. Which means at this rate I won't finish the book for three more months. I still hold the opinion of my last post...that the book is great, and quite humorous. I love the concept of Thackeray's narrator, who is Thackeray himself, and who comes out from the pages to constantly remind you that this is a novel and that he's made up the plot and the characters. No, my slow pace is not due to the book, but due to my hectic work schedule of late, and my travels to the midwest (to visit family) and now to suburban Maryland, near Washington, DC (for work). Turns out the area around Washington, DC is a huge suburb/exurb. Well, at least where I am. I'm surrounded by chain hotels, office parks, and shopping malls. Granted, the malls are pretty upscale, and the landscape is lush with green, and deer everywhere, even by the side of busy highways. It's a wonder there's not more deer carnage on the roads around here. But I digress...big time...

The novel is subtitled "A novel without a hero" and even after 140 pages it's clear that will be true. The novel's characters are all flawed in some way, usually deeply flawed. Some are ruthless and some are clueless, but none of them are like the idyllic or angelic characters you'll occasionally find in Dickens (I'm talking to you, Esther Summerson). But isn't that how life is...who among us knows anyone without flaws? I rest my case.

The story is rambling at times...much like this particular blog post. It's hard to see how Thackeray is going to milk this puppy for another 548 pages. Well, scratch that...yes, from the story's rambling nature so far it is indeed clear how this is going to happen. But I don't care. It's funny, it's a good read, and it's not at all clear how it's going to end up. But I'm keeping a close eye on Becky Sharp. I'm guessing that more antics will ensue, and she'll be at the center of it all. Stay tuned.

Tuesday, October 7, 2008

Holy F#&k!!

Ok, here's the deal. Normally I wouldn't comment on a book when I'm only nine pages into it, but here I have to make an exception. I started reading "Vanity Fair" (William Makepeace Thackeray) tonight, and got through the first chapter plus intro, and I am dumbstruck...with laughter! If this book can keep this up, then I'm gonna be totally blown away. It's hilarious! First of all there's the introduction which strikes me as almost "postmodern"...and I use that word in quotes because frankly, as a scientist, I believe that no one really knows that the word means. In the introduction, the author says, basically, "Check this story out, you huddled mass of humanity...I made it all up! It's nothing but a puppet show...weee, here we go, mother f#%ers! Ha, ha! No, but seriously...".

In Chapter 1, we learn that Miss Amelia Sedley and Miss Becky Tharp are graduating from Miss Pinkerton's academy for young ladies. Actually, Miss Sedley is graduating, and Miss Tharp is leaving for reasons as yet unclear, but graduation does not seem to be one of them. The chapter describes the scene of the two leaving the school. Both are given copies of Dr. Johnson's dictionary, since Miss Pinkerton seems to have met the good doctor at some point, and has held on to this as her claim to fame. Becky ends up throwing her copy out of the coach as they drive away from the school. Hmm, I think I'll like her. But what really cracked me up is that Thackeray writes this in the third person, but comes out from behind the narrator's voice to play the puppet master. First of all, he rags on the characters, calling Miss Pinkerton a "pompous old Minerva of a woman". I'm not quite sure what that means (and yes I looked up Minerva on Wikipedia), but the point is clear. And then, after describing in detail the students' reaction to Amelia's farewell, he writes:

All which details, I have no doubt, JONES, who reads this book at his Club, will pronounce to be excessively foolish, trivial, twaddling, and ultra-sentimental. Yes; I can see Jones at this minute (rather flushed with his joint of mutton and half-pint of wine), taking out his pencil and scoring under the words "foolish, twaddling," &c., and adding to them his own remark "quite true." Well, he is a lofty man of genius, and admires the great and heroic in life and novels; and so had better take warning and go elsewhere.

Woah! This is so awesome!! First of all, I love how JONES is capitalized! WTF? Then, in a couple of sentences, he manages to not only rag on Jones, but to rag on his own book as well. If that isn't postmodern, what is? Hmm, who thought Victorian literature was postmodern? And don't tell me I don't know what postmodernism is, because you don't either! But we already discussed that point.

Anyway, I don't plan on blogging after EVERY chapter of this book, but if it continues to be so awesome I may have little choice.

Sunday, October 5, 2008

Book #24 - Up From Slavery (Booker T. Washington)

"Up from Slavery" is a classic piece of Americana that I suspect is not read as much as it used to be. It is the autobiography of Booker T. Washington, who rose from being a slave to becoming arguably the most dominant black spokesperson at the beginning of the twentieth century.

He was born around 1858, although he is not sure of the exact year or date. His mother was a plantation worker in Virginia. His father was a white man who lived nearby. He says his owners were not especially cruel compared to others, but since he refuses to speak badly of anyone in this book, that may be taken with a grain of salt. He was six or seven when the Civil War ended and he and his family were freed. This was one of the more interesting anecdotes in the book. He writes that all the slaves knew the war was going badly for the south, which meant they would soon be free. Deserting soldiers were a common sight along the roads. One day an announcement came that all the slaves should gather at the plantation house. The master and his family were all there, as was a uniformed officer. The officer read a long paper, presumably the Emancipation Proclamation, and then announced that all the slaves were free and could go when and where they pleased. Everyone rejoiced, and there were "wild scenes of ecstasy". But that didn't last...by the time the slaves returned to their cabins, it began to dawn on them that they suddenly had responsibility for their lives, and didn't really know what to do. All that evening, many of the former slaves quietly went back to the plantation house to have whispered conversations with their former owner. Booker even writes that the slaves felt sorry for their former owner and his family. Again, though, I have a hard time believing this. One of the problems I had with this book is that it is relentlessly, almost painfully optimistic. Clearly Booker wants peace and harmony between the races, and he takes great pains to disparage no one. To the modern ear this seems to ring a bit false. But was it? Was he really this optimistic and altruistic? Surely he must have encountered terrible prejudice at times, yet he doesn't report this, and throughout the book goes to great lengths to explain how white people have helped him, his cause (we'll get to that), and his race throughout his life.

But I digress. After being freed, Booker's mother got married and the family moved to Malden, West Virginia, where Booker's stepfather worked in the coal mines. Booker himself started working in the mines, but that didn't last for more than a few years. He had an almost insatiable thirst for education and learning, and studied as much as he could on his own at night. Booker was the exact opposite of a slacker. His relentless drive to work, learn, and succeed were unbelievable. He eventually made his way to the Hampton Institute in Virginia, which had been set up as a school for freed slaves. He convinced the school to let him in, agreeing to do janitorial work full time to pay for his schooling. He eventually graduated, winning the admiration of the school's white president, Samuel Armstrong. After attending Wayland Seminary to learn to become a teacher, Booker was recommended by Samuel Armstrong to head up a new school for freed slaves in Tuskegee, Alabama. While these posts were usually held by whites, the school's founders took Armstrong up on his recommendation, and asked Booker to head up the school at the age of 25. He would head the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) for the rest of his life.

The first third of the book details Booker's childhood and education, while the second third or so details his work in building up Tuskegee from a shack into a major educational institution. Two things stand out. First, he firmly believed that not only should students learn in the usual sense (classes, books) but that they should also work themselves through school, and learn a trade. Unbelievably, most of the buildings erected at Tuskegee over the years were built by the students. The students also made the bricks for the buildings, and ran a farm that grew the food for the school. Booker believed that black people needed to learn trades to be able to support themselves, and that if whites could see that blacks were hard-working assets to their communities, they would be more accepted into American society. This became somewhat controversial within the African American community (and this is not mentioned in the book). Prominent write W.E. DuBois argued that blacks should get the same liberal arts education as whites, and that a well-educated black vanguard would help push the cause for civil rights. In DuBois's mind, focusing an education on the industrial arts was holding blacks to a limited set of options.

The second thing that stands out about Washington's work at Tuskegee is that much of his time was spent in soliciting funds for the school. He starts out in the local community, asking for money from both blacks and whites. He works hard to build up relationships with the local white people so that they will look upon the school with pride, and thus be more likely to donate to it. And he starts traveling to the northeast, seeking donations from philanthropists. He must have been an extremely persuasive and charming person, because he totally succeeds. He builds up a large network of donors, and hobnobs with the likes of Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and others.

The last third of the book details Washington's accounts of traveling to visit donors, and giving speeches. He became quite famous as an orator, and delivered one of America's most famous speeches at an exhibition in Atlanta in 1895. The "Atlanta Compromise" speech encouraged whites to hire black workers and accept them into local communities. He also argues that agitating for social equality is "extremist folly". Other would disagree with this, but white people were soothed, and the speech was a turning point in Washington's ability to raise more money for Tuskegee and black education. This last part of the book I found not nearly as interesting as the first 2/3 of the book...Booker's struggles for success have ended, so it's just not as interesting. Plus, there's that relentless optimism, praising this person and that person as the greatest person ever to walk the earth. He sounds like he's plugging something, which I guess, in effect, he was. After all, you can't expect donations from people if you put them or their friends down in your autobiography. Because of this relentless optimism, it's clear this book was written at the beginning, rather than the end, of the twentieth century...the mood and tone seem a bit dated now. Regardless, it offers a unique glimpse into the years when African Americans were recently released from slavery...at least for the first 2/3 of the book.

Next on my list...it's back to Victorian England!

Saturday, September 27, 2008

Book #23 - Things Fall Apart (Chinua Achebe)

When I was compiling the list of the greatest books I'd never read, I found this one on a lot of "top 100 novels ever" lists. And yet I'd never heard of it, nor the author. So right away I was looking forward to it. And it didn't disappoint. This is a great book, a disturbing book, a tragic story, and an important book for anyone wanting to understand Africa before and after its colonization by Europeans. This is a book that I'll want to read again at some point. The language of the book is deceptively simple, but the ideas it presents are complex and multifaceted, which is a tribute to Achebe's talent.

The book tells the story of Okonkwo, a member of the Igbo tribe in the village of Umuofia in pre-colonial Nigeria. Okonkwo is a bitter, angry man, full of rage. His father was a lazy man, who preferred to play his flute rather than repay his many debts. Okonkwo grew up ashamed of his father, and vows to become the opposite of his father: a strong man, a leader respected by his entire tribe. He works hard, and through his hard work and his athletic prowess he indeed becomes a respected member of the community. Of course, he also has a lot of repressed anger, which means he cannot show his feelings towards his children and he sometimes beats his three wives. This repressed anger will prove to be his downfall.

The structure of this book is interesting. The first two thirds or so of the story deal with Okonkwo and his life in the tribal village of Umuofia. The customs and religion of the Igbo tribe are described in detail. Despite no written language, they have a sophisticated culture of complex beliefs, many of which are directed towards resolving conflicts peacefully. They also have a rich folklore, through which wisdom is passed down to their children. Then, in the last third of the book, the missionaries arrive, followed soon by the white man's colonial government. And things then do fall apart. The native culture and way of life is changed and destroyed. And Okonkwo meets his downfall, although the seeds of his downfall were sown way before the white people arrived.

At first, the villagers just thought the missionaries were crazy...spouting weird ideas about their one God, who seemed much less powerful than the Igbo gods. But some of the members of the tribe were attracted to the religion the missionaries preached. Some, like one of Okonkwo's sons, found something in the religious preachings of the missionaries that filled gaps in their spiritual lives. Others were outsiders and outcasts in the village culture, and they found in the Christian church that they were all equals, and that, naturally, appealed to them. And so the church grew. Once the Igbo people were divided into those that accepted the new religion, and those that did not, the tribe was fatally weakened. After the missionaries settled in, other white people arrived, who brought schools and medicine, and the Igbo people could see the value in these. They also learned that if they resisted, they would be wiped out, which happened to one of the first villages to make contact with the white people. Thus, the tribe adjusted to the new ways, and lost their old. The new technology and knowledge brought by the Europeans was simply too powerful to resist.

Okonkwo is a man strongly rooted in his tribe's tradition. He seeks status, and manliness, in the traditional sense of his community. He is forced into several terrible circumstances by the tribe's laws and religion. Yet he obeys the tribe's rules and gods because he wants the respect of his fellow tribesmen. When the local priest tells Okonkwo that his adopted son, who was taken from a neighboring tribe as settlement for a dispute several year earlier, must be killed, Okonkwo not only agrees but ends up killing the boy himself so as not to look unmanly (This act ultimately helps push his oldest son away and into the arms of the missionary church, since he was quite attached to his adopted brother and could never forgive his father). When Okonkwo accidently kills a tribesmen, he accepts the tribe's traditional punishment of seven years exile. And after he returns from exile he urges his tribe to go to war with the white man, because to not do so would be unmanly and weak. Yet Okonkwo seems more interested in his own status and perceived manhood than he is in the welfare of his village as a whole. The white people threaten the place in tribe's society that he has worked all his life for. So he urges his fellow tribesmen to resist the white people, to fight back, even though they have learned that accommodation is the best way to survive in the changed world. I won't give a spoiler here and say what happens to Okonkwo except that, well, it's dark result.

This book was written in 1959, at a time when the stories of the colonization of Africa were told by Europeans like Joseph Conrad. This book tells the story from the opposite perspective, from the African's point of view. It's a complex perspective that Achebe presents, however. He does not take a black and white view...the white people aren't all bad and the black people all good. He pokes fun, at times, of the Igbo culture and customs, and there is one white missionary minister who is a very sympathetic character...and as I mention above, some of the tribes people found great comfort in the new religion. But overall, the devastation of the Igbo culture by the whites is made clear, and the Achebe pulls no punches in the last paragraph of the book. Okonkwo is a man with a tragic flaw, which leads him to tragedy, but his personal tragedy is only one part of a larger cultural tragedy.

Sunday, September 21, 2008

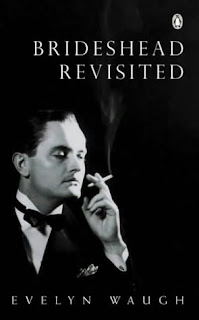

Book #22 - Brideshead Revisited (Evelyn Waugh)

"Brideshead Revisited" has been made into about five movies over the past decade or so, apparently all of them starring Jeremy Irons. Or so it seems. Fortunately I have not seen any of these, so I had no idea what this book was about when I picked it up, which is generally the way I like it. Here's what it turned out to be about: booze, rich people, and religion, specifically Catholicism.

The narrator and main character of the book is Charles Ryder. The novel opens with Ryder an officer in England during World War II. In the book's prologue, his company is sent to a new camp in the English countryside, and it turns out to be on an estate of the Flyte family, whom he knows quite well. The story of the novel is then told in flashback form. And that story is all about Charles's relationships with the Flyte family. The Flytes are an old, aristocratic family, with a huge estate (Brideshead) and a lot of money, although we learn in the course of the novel that that money is diminishing. The Flytes are Catholic, not the norm in Protestant England, and their relationship to Catholicism forms one of the cruxes of the novel.

As the story opens, Charles is a freshman at Oxford University. One evening, as he's hanging out with friends in his room (or suite of rooms...the characters in the novel all lived in style), a drunken student sticks his head in Charles's first floor window and, as students would say, ralphs. Charles is understandably a bit put off by this, but the student, Sebastian Flyte, is profusely apologetic, sends flowers, and invites Charles to lunch. They are soon inseparable. Sebastian is incredibly charming, loves to party, and carries a stuffed bear named Aloysius with him everywhere. He introduces Charles to his small circle of friends, all hedonistic wits and heavy drinkers. In other words, the kind of people we all wish we'd hung out with in college. Charles and Sebastian become very close, and it's a mystery as to exactly how close. Is their relationship platonic only, or is there a physical element? We never really know, although I don't think it's critical that we do know. Their relationship is close, and they bond intensely. It's what kids today would call a "bromance".

Sebastian brings Charles to Brideshead where he meets the rest of the Flyte family. Well, most of it anyway. Sebastian's parents are separated, with the father, Lord Marchmain, living in Venice with his mistress, while the mother, Lady Marchmain, lives at Brideshead with her older son, Brideshead, and her two daughters, Julia and Cordelia. The family are all oddballs, in their own way. The mother is fiercely Catholic, which causes Sebastian to rebel (i.e. reject Catholicism). Julia is engaged to Rex Mottram, a Canadian who is clearly a pompous and empty buffoon, albeit a wealthy one. Julia is not religious, having given up the Catholic church like Sebastian. Cordelia, the youngest, is fiercely Catholic like her mother. And Brideshead (the son, not the estate) is just odd...somewhat shy, not totally comfortable in social situations. In the later part of the novel he becomes an avid collector of matchboxes.

The summer before school Sebastian and Charles travel to Venice to see Sebastian's father. While they are there, the father's mistress says privately to Charles that even though he and Sebastian both love to drink, she can tell that it's different with Sebastian, that he can't control it. She proves to be quite prescient. As they enter their second year at Oxford, Sebastian's drinking indeed becomes a problem. He's failing his school work, staying out late, and drunk most of the time. He and Charles visit the Flytes at Brideshead over the holidays and things are really falling apart...Sebastian is always drunk, and makes a few scenes. The family tries to keep the booze away from him, but it doesn't work. He drops out of Oxford and takes off. Charles only sees him again once or twice. He eventually makes his way to Morocco, sick and drunk, and ends up living in a monastery. We don't hear from him again.

Sebastian's drinking problem is tragic and sad, especially given his wonderful personality and his youthful promise at the story's start. But his story rings true. I knew many heavy drinkers in college (after all, isn't that the definition of a college student?), and there were a few that were clearly destined for problems. Somehow you could tell them apart...they had a deeper need for drinking than most people, and were clearly marked for trouble. Who knows why some are touched but not others.

Perhaps it's ironic that I'm sipping on some Guatemalan rum as I write this.

Charles ends up dropping out of Oxford to go to art school, and becomes a painter. He's an architectural painter, painting portraits of houses of wealthy aristocrats for commissions. We're lead to believe he has talent, but is by no means a great artist. He marries, and has a couple of kids, and takes off to South America to paint for two years after his wife has an affair. Despite the affair, it doesn't seem like he was ever close to his wife (of course the affair was probably a symptom that it was mutual). On his return to Europe he meets Julia Flyte on the ship. Julia is now separated from Rex, who she can't stand anymore...a year or two of marriage to him was enough for her to realize how empty he was. She and Charles begin to have an affair. Charles was always attracted to Julia, not in the least because she looked like Sebastian. They fall in love, and make plans to marry after they both get divorced. Could this novel end up ending happily? Yeah, right...the tone is way too bittersweet for that to happen.

So here's what happens: Lady Flyte has died, which allows Lord Flyte to come back to Brideshead (he couldn't come while she was alive because he absolutely could not stand her anymore). When he returns, he's quite ill and is slowly dying with heart failure. This produces a conflict between the children (Julia, Brideshead, and Cordelia). Should they bring in a priest to give the father his last rites? The father had been Anglican, but converted to Catholicism to satisfy his wife. But when they separated (25 years earlier) he left the church, and felt no attachment to it. The children decide they want a priest to come and see the father (even Julia, who had been a lapsed Catholic). Charles is against this, but what can he do? So a priest comes, and the father throws him out. But then the father gets sicker and is finally very close to death. This sets up the most poignant scene of the novel. The children bring in the priest again, and he gives their father his last rites. They pray that the father will give them some sign, and the father crosses himself. A few hours later he dies. Both Julia and Charles are deeply affected. Charles, who had been totally against the priest giving their father his last rites, on the grounds that the father did not want it, seems to have a religious experience while they're around the deathbed. He fervently prays for God to forgive the father's sins, and he is deeply moved when the father crosses himself. This is the first time in the novel that he's shown any religious inkling at all. After the father dies, Julia comes to Charles and says she cannot marry him. Charles says he understands. They part ways. End of story...well, not quite, as there's an epilogue back in the "present" World War II days.

Upon first reading this I was like "What the f&#$ just happened? Why won't Julia marry him?". But the I realized it was all about religion. Charles was divorced, and she had been having an affair with him, both really bad things in the eyes of the Catholic church. Julia, newly repentant and a Catholic again, had to reject him. Charles, having had his religious experience, recognizes and accepts this. While intellectually I can understand where they're coming from, it's hard for me to emotionally relate to this. I'm not from a religious family, so taking ones religion so seriously as to not marry the person you love because the church doesn't like that they were divorced...well, it makes a good story, I guess, but it's definitely outside the realm of my emotional comprehension.

This book reminded me, ever so slightly, of Thomas Mann's "Buddenbrooks", which I read years ago. That book is about the decline of a German upper middle class family. This book is also about a family in decline, in it's own peculiar way. The days of aristocracy are waning, and the family members all lead saddened lives (some sadder than others). And in fact, one of the things that attracts Charles to Julia is her sadness. None of the family members faces a particularly prosperous future. At the end, each of them in their own way finds solace in their religion, but in the end, their lives are still sad. As is Charles's. Not tragic, or catastrophic, just sad and wistful. Sigh...if only they had kept Aloysius around...

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Book #21 - Moll Flanders (Daniel Defoe)

My reading for this project has so far been pretty scattershot, rambling from one author to another in no order whatsoever, just flowing along wherever the streams of whiskey may take me. But I enjoyed "Robinson Crusoe" and "Journal of the Plague Year" so much, that I decided to immediately tackle the last Defoe novel on my list, "Moll Flanders". And I'm glad I did! Of all the three Defoe novels, I have to say I enjoyed this one the most.

The full title of "Moll Flanders" is "The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders, who was born in Newgate, and during a life of continu'd variety of threescore years, besides her childhood, was twelve years a whore, five times a wife (whereof once to her own brother), twelve year a thief, eight year a transported felon in Virginia, at last grew rich, liv'd honest, and died a penitent". Damn...they certainly didn't leave anything out of the title in those days. I guess the title back then was the equivalent to the modern day dust jacket...something to get you interested enough to buy the book. Certainly the full title here caught my interest. Of course, it also gives away the entire plot of the book.

I have to give Defoe tremendous kudos for coming up with great ideas for his books. Stranded on a deserted island, watching while all around half of a major city's population dies of a horrible epidemic, and the close-up and personal life story of a woman who is, well, see the full title above. These are all such great ideas...how could anyone not want to read these books, especially in olden times before the invention of the PlayStation distracted everyone?

As the title says, the narrator and main character of this novel is Moll Flanders (not her real name), who is born in Newgate prison as her mother is a convicted criminal. After Moll is born, mom is shipped off to Virginia, and Moll has to fend for herself. After living with gypsies for awhile, she's taken in by some local women, and eventually lives with a family as a maid. She grows to be quite beautiful, and one of the brothers of the house seduces her. They have a fling, and he promises to marry her, but he also always leaves her money after they have sex. Soon the younger brother falls in love with her, even though Moll scorns his advances, and eventually proposes to her. When Moll asks the older brother what to do, he tells her that he wasn't really serious about marrying her, and she should marry the younger brother. Moll's pretty ticked off about this, but eventually relents and marries the younger brother. They have a couple of kids, and five years later he dies. The two kids are sent to live with the husband's parents, and Moll takes off. This is not the last time in the book that she has children and then abandons them. In fact, I lost count of how many children she had, and then abandoned.

Anyway, Moll's adventures in men continue. She marries a draper (I'm guessing that's someone who makes drapes??), but after spending them into poverty, he gets arrested and flees abroad. He tells her she should pretend that she's not married because he'll never be back. Ah well. Moll then meets another man, who's wealthy, and she tricks him into believing that she's wealthy too. They marry, and then she breaks the news to him. Fortunately he loves her, and he takes her to Virginia where he has a plantation. They have children, and live with his mom, and they're happy, That is until Moll discovers that his mom is also her mom, and thus she's married her half brother. Oops. So, she flees back to England, with her husband/brother and her both agreeing to pretend the other one has died and they're no longer married (remember, this was in the days before the IRS had everyone in their database). Back in England, Moll has an affair with a married man whose wife has gone insane, and has several children by him (who are, that's right, are eventually abandoned by Moll with little fanfare).

After the married man affair falls through, Moll is courted by a married banker, who tells her he'll get a divorce to be with her, as his wife cheated on him. Moll says she'll think about it once he's actually divorced. Then Moll goes to the country where she meets and is courted by a wealthy gentleman, whom she deceives into thinking she's wealthy as well (hmm, seems to be a pattern with her). They marry, and then both discover that neither one is rich, and that they were both deceiving one another. They have a good laugh and get along famously. They are indeed two of a kind. But soon the husband, Jemy, runs away to Ireland to seek his fortune, and Moll doubts she'll see him again. So she decides to marry the banker, who's now divorced, but since she's pregnant again, she must wait to have her baby. Her landlord turns her on to a woman ("the governess") who runs a boarding house for ladies in trouble. This lady helps out Moll, and pays a woman to take away her baby once it's born (I didn't quite understand this part. Didn't they have adoption back then? Moll was quite worried the child would come to harm, but to her credit she follows up and makes sure it's OK with the new family). So Moll is now free to marry the banker, which she does. They live happily for a few years, until he loses all his money in speculation and then dies. Damn, Moll can't catch a break!