When I was compiling the list of the greatest books I'd never read, I found this one on a lot of "top 100 novels ever" lists. And yet I'd never heard of it, nor the author. So right away I was looking forward to it. And it didn't disappoint. This is a great book, a disturbing book, a tragic story, and an important book for anyone wanting to understand Africa before and after its colonization by Europeans. This is a book that I'll want to read again at some point. The language of the book is deceptively simple, but the ideas it presents are complex and multifaceted, which is a tribute to Achebe's talent.

The book tells the story of Okonkwo, a member of the Igbo tribe in the village of Umuofia in pre-colonial Nigeria. Okonkwo is a bitter, angry man, full of rage. His father was a lazy man, who preferred to play his flute rather than repay his many debts. Okonkwo grew up ashamed of his father, and vows to become the opposite of his father: a strong man, a leader respected by his entire tribe. He works hard, and through his hard work and his athletic prowess he indeed becomes a respected member of the community. Of course, he also has a lot of repressed anger, which means he cannot show his feelings towards his children and he sometimes beats his three wives. This repressed anger will prove to be his downfall.

The structure of this book is interesting. The first two thirds or so of the story deal with Okonkwo and his life in the tribal village of Umuofia. The customs and religion of the Igbo tribe are described in detail. Despite no written language, they have a sophisticated culture of complex beliefs, many of which are directed towards resolving conflicts peacefully. They also have a rich folklore, through which wisdom is passed down to their children. Then, in the last third of the book, the missionaries arrive, followed soon by the white man's colonial government. And things then do fall apart. The native culture and way of life is changed and destroyed. And Okonkwo meets his downfall, although the seeds of his downfall were sown way before the white people arrived.

At first, the villagers just thought the missionaries were crazy...spouting weird ideas about their one God, who seemed much less powerful than the Igbo gods. But some of the members of the tribe were attracted to the religion the missionaries preached. Some, like one of Okonkwo's sons, found something in the religious preachings of the missionaries that filled gaps in their spiritual lives. Others were outsiders and outcasts in the village culture, and they found in the Christian church that they were all equals, and that, naturally, appealed to them. And so the church grew. Once the Igbo people were divided into those that accepted the new religion, and those that did not, the tribe was fatally weakened. After the missionaries settled in, other white people arrived, who brought schools and medicine, and the Igbo people could see the value in these. They also learned that if they resisted, they would be wiped out, which happened to one of the first villages to make contact with the white people. Thus, the tribe adjusted to the new ways, and lost their old. The new technology and knowledge brought by the Europeans was simply too powerful to resist.

Okonkwo is a man strongly rooted in his tribe's tradition. He seeks status, and manliness, in the traditional sense of his community. He is forced into several terrible circumstances by the tribe's laws and religion. Yet he obeys the tribe's rules and gods because he wants the respect of his fellow tribesmen. When the local priest tells Okonkwo that his adopted son, who was taken from a neighboring tribe as settlement for a dispute several year earlier, must be killed, Okonkwo not only agrees but ends up killing the boy himself so as not to look unmanly (This act ultimately helps push his oldest son away and into the arms of the missionary church, since he was quite attached to his adopted brother and could never forgive his father). When Okonkwo accidently kills a tribesmen, he accepts the tribe's traditional punishment of seven years exile. And after he returns from exile he urges his tribe to go to war with the white man, because to not do so would be unmanly and weak. Yet Okonkwo seems more interested in his own status and perceived manhood than he is in the welfare of his village as a whole. The white people threaten the place in tribe's society that he has worked all his life for. So he urges his fellow tribesmen to resist the white people, to fight back, even though they have learned that accommodation is the best way to survive in the changed world. I won't give a spoiler here and say what happens to Okonkwo except that, well, it's dark result.

This book was written in 1959, at a time when the stories of the colonization of Africa were told by Europeans like Joseph Conrad. This book tells the story from the opposite perspective, from the African's point of view. It's a complex perspective that Achebe presents, however. He does not take a black and white view...the white people aren't all bad and the black people all good. He pokes fun, at times, of the Igbo culture and customs, and there is one white missionary minister who is a very sympathetic character...and as I mention above, some of the tribes people found great comfort in the new religion. But overall, the devastation of the Igbo culture by the whites is made clear, and the Achebe pulls no punches in the last paragraph of the book. Okonkwo is a man with a tragic flaw, which leads him to tragedy, but his personal tragedy is only one part of a larger cultural tragedy.

Saturday, September 27, 2008

Book #23 - Things Fall Apart (Chinua Achebe)

Sunday, September 21, 2008

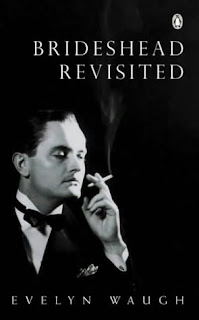

Book #22 - Brideshead Revisited (Evelyn Waugh)

"Brideshead Revisited" has been made into about five movies over the past decade or so, apparently all of them starring Jeremy Irons. Or so it seems. Fortunately I have not seen any of these, so I had no idea what this book was about when I picked it up, which is generally the way I like it. Here's what it turned out to be about: booze, rich people, and religion, specifically Catholicism.

The narrator and main character of the book is Charles Ryder. The novel opens with Ryder an officer in England during World War II. In the book's prologue, his company is sent to a new camp in the English countryside, and it turns out to be on an estate of the Flyte family, whom he knows quite well. The story of the novel is then told in flashback form. And that story is all about Charles's relationships with the Flyte family. The Flytes are an old, aristocratic family, with a huge estate (Brideshead) and a lot of money, although we learn in the course of the novel that that money is diminishing. The Flytes are Catholic, not the norm in Protestant England, and their relationship to Catholicism forms one of the cruxes of the novel.

As the story opens, Charles is a freshman at Oxford University. One evening, as he's hanging out with friends in his room (or suite of rooms...the characters in the novel all lived in style), a drunken student sticks his head in Charles's first floor window and, as students would say, ralphs. Charles is understandably a bit put off by this, but the student, Sebastian Flyte, is profusely apologetic, sends flowers, and invites Charles to lunch. They are soon inseparable. Sebastian is incredibly charming, loves to party, and carries a stuffed bear named Aloysius with him everywhere. He introduces Charles to his small circle of friends, all hedonistic wits and heavy drinkers. In other words, the kind of people we all wish we'd hung out with in college. Charles and Sebastian become very close, and it's a mystery as to exactly how close. Is their relationship platonic only, or is there a physical element? We never really know, although I don't think it's critical that we do know. Their relationship is close, and they bond intensely. It's what kids today would call a "bromance".

Sebastian brings Charles to Brideshead where he meets the rest of the Flyte family. Well, most of it anyway. Sebastian's parents are separated, with the father, Lord Marchmain, living in Venice with his mistress, while the mother, Lady Marchmain, lives at Brideshead with her older son, Brideshead, and her two daughters, Julia and Cordelia. The family are all oddballs, in their own way. The mother is fiercely Catholic, which causes Sebastian to rebel (i.e. reject Catholicism). Julia is engaged to Rex Mottram, a Canadian who is clearly a pompous and empty buffoon, albeit a wealthy one. Julia is not religious, having given up the Catholic church like Sebastian. Cordelia, the youngest, is fiercely Catholic like her mother. And Brideshead (the son, not the estate) is just odd...somewhat shy, not totally comfortable in social situations. In the later part of the novel he becomes an avid collector of matchboxes.

The summer before school Sebastian and Charles travel to Venice to see Sebastian's father. While they are there, the father's mistress says privately to Charles that even though he and Sebastian both love to drink, she can tell that it's different with Sebastian, that he can't control it. She proves to be quite prescient. As they enter their second year at Oxford, Sebastian's drinking indeed becomes a problem. He's failing his school work, staying out late, and drunk most of the time. He and Charles visit the Flytes at Brideshead over the holidays and things are really falling apart...Sebastian is always drunk, and makes a few scenes. The family tries to keep the booze away from him, but it doesn't work. He drops out of Oxford and takes off. Charles only sees him again once or twice. He eventually makes his way to Morocco, sick and drunk, and ends up living in a monastery. We don't hear from him again.

Sebastian's drinking problem is tragic and sad, especially given his wonderful personality and his youthful promise at the story's start. But his story rings true. I knew many heavy drinkers in college (after all, isn't that the definition of a college student?), and there were a few that were clearly destined for problems. Somehow you could tell them apart...they had a deeper need for drinking than most people, and were clearly marked for trouble. Who knows why some are touched but not others.

Perhaps it's ironic that I'm sipping on some Guatemalan rum as I write this.

Charles ends up dropping out of Oxford to go to art school, and becomes a painter. He's an architectural painter, painting portraits of houses of wealthy aristocrats for commissions. We're lead to believe he has talent, but is by no means a great artist. He marries, and has a couple of kids, and takes off to South America to paint for two years after his wife has an affair. Despite the affair, it doesn't seem like he was ever close to his wife (of course the affair was probably a symptom that it was mutual). On his return to Europe he meets Julia Flyte on the ship. Julia is now separated from Rex, who she can't stand anymore...a year or two of marriage to him was enough for her to realize how empty he was. She and Charles begin to have an affair. Charles was always attracted to Julia, not in the least because she looked like Sebastian. They fall in love, and make plans to marry after they both get divorced. Could this novel end up ending happily? Yeah, right...the tone is way too bittersweet for that to happen.

So here's what happens: Lady Flyte has died, which allows Lord Flyte to come back to Brideshead (he couldn't come while she was alive because he absolutely could not stand her anymore). When he returns, he's quite ill and is slowly dying with heart failure. This produces a conflict between the children (Julia, Brideshead, and Cordelia). Should they bring in a priest to give the father his last rites? The father had been Anglican, but converted to Catholicism to satisfy his wife. But when they separated (25 years earlier) he left the church, and felt no attachment to it. The children decide they want a priest to come and see the father (even Julia, who had been a lapsed Catholic). Charles is against this, but what can he do? So a priest comes, and the father throws him out. But then the father gets sicker and is finally very close to death. This sets up the most poignant scene of the novel. The children bring in the priest again, and he gives their father his last rites. They pray that the father will give them some sign, and the father crosses himself. A few hours later he dies. Both Julia and Charles are deeply affected. Charles, who had been totally against the priest giving their father his last rites, on the grounds that the father did not want it, seems to have a religious experience while they're around the deathbed. He fervently prays for God to forgive the father's sins, and he is deeply moved when the father crosses himself. This is the first time in the novel that he's shown any religious inkling at all. After the father dies, Julia comes to Charles and says she cannot marry him. Charles says he understands. They part ways. End of story...well, not quite, as there's an epilogue back in the "present" World War II days.

Upon first reading this I was like "What the f&#$ just happened? Why won't Julia marry him?". But the I realized it was all about religion. Charles was divorced, and she had been having an affair with him, both really bad things in the eyes of the Catholic church. Julia, newly repentant and a Catholic again, had to reject him. Charles, having had his religious experience, recognizes and accepts this. While intellectually I can understand where they're coming from, it's hard for me to emotionally relate to this. I'm not from a religious family, so taking ones religion so seriously as to not marry the person you love because the church doesn't like that they were divorced...well, it makes a good story, I guess, but it's definitely outside the realm of my emotional comprehension.

This book reminded me, ever so slightly, of Thomas Mann's "Buddenbrooks", which I read years ago. That book is about the decline of a German upper middle class family. This book is also about a family in decline, in it's own peculiar way. The days of aristocracy are waning, and the family members all lead saddened lives (some sadder than others). And in fact, one of the things that attracts Charles to Julia is her sadness. None of the family members faces a particularly prosperous future. At the end, each of them in their own way finds solace in their religion, but in the end, their lives are still sad. As is Charles's. Not tragic, or catastrophic, just sad and wistful. Sigh...if only they had kept Aloysius around...

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Book #21 - Moll Flanders (Daniel Defoe)

My reading for this project has so far been pretty scattershot, rambling from one author to another in no order whatsoever, just flowing along wherever the streams of whiskey may take me. But I enjoyed "Robinson Crusoe" and "Journal of the Plague Year" so much, that I decided to immediately tackle the last Defoe novel on my list, "Moll Flanders". And I'm glad I did! Of all the three Defoe novels, I have to say I enjoyed this one the most.

The full title of "Moll Flanders" is "The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders, who was born in Newgate, and during a life of continu'd variety of threescore years, besides her childhood, was twelve years a whore, five times a wife (whereof once to her own brother), twelve year a thief, eight year a transported felon in Virginia, at last grew rich, liv'd honest, and died a penitent". Damn...they certainly didn't leave anything out of the title in those days. I guess the title back then was the equivalent to the modern day dust jacket...something to get you interested enough to buy the book. Certainly the full title here caught my interest. Of course, it also gives away the entire plot of the book.

I have to give Defoe tremendous kudos for coming up with great ideas for his books. Stranded on a deserted island, watching while all around half of a major city's population dies of a horrible epidemic, and the close-up and personal life story of a woman who is, well, see the full title above. These are all such great ideas...how could anyone not want to read these books, especially in olden times before the invention of the PlayStation distracted everyone?

As the title says, the narrator and main character of this novel is Moll Flanders (not her real name), who is born in Newgate prison as her mother is a convicted criminal. After Moll is born, mom is shipped off to Virginia, and Moll has to fend for herself. After living with gypsies for awhile, she's taken in by some local women, and eventually lives with a family as a maid. She grows to be quite beautiful, and one of the brothers of the house seduces her. They have a fling, and he promises to marry her, but he also always leaves her money after they have sex. Soon the younger brother falls in love with her, even though Moll scorns his advances, and eventually proposes to her. When Moll asks the older brother what to do, he tells her that he wasn't really serious about marrying her, and she should marry the younger brother. Moll's pretty ticked off about this, but eventually relents and marries the younger brother. They have a couple of kids, and five years later he dies. The two kids are sent to live with the husband's parents, and Moll takes off. This is not the last time in the book that she has children and then abandons them. In fact, I lost count of how many children she had, and then abandoned.

Anyway, Moll's adventures in men continue. She marries a draper (I'm guessing that's someone who makes drapes??), but after spending them into poverty, he gets arrested and flees abroad. He tells her she should pretend that she's not married because he'll never be back. Ah well. Moll then meets another man, who's wealthy, and she tricks him into believing that she's wealthy too. They marry, and then she breaks the news to him. Fortunately he loves her, and he takes her to Virginia where he has a plantation. They have children, and live with his mom, and they're happy, That is until Moll discovers that his mom is also her mom, and thus she's married her half brother. Oops. So, she flees back to England, with her husband/brother and her both agreeing to pretend the other one has died and they're no longer married (remember, this was in the days before the IRS had everyone in their database). Back in England, Moll has an affair with a married man whose wife has gone insane, and has several children by him (who are, that's right, are eventually abandoned by Moll with little fanfare).

After the married man affair falls through, Moll is courted by a married banker, who tells her he'll get a divorce to be with her, as his wife cheated on him. Moll says she'll think about it once he's actually divorced. Then Moll goes to the country where she meets and is courted by a wealthy gentleman, whom she deceives into thinking she's wealthy as well (hmm, seems to be a pattern with her). They marry, and then both discover that neither one is rich, and that they were both deceiving one another. They have a good laugh and get along famously. They are indeed two of a kind. But soon the husband, Jemy, runs away to Ireland to seek his fortune, and Moll doubts she'll see him again. So she decides to marry the banker, who's now divorced, but since she's pregnant again, she must wait to have her baby. Her landlord turns her on to a woman ("the governess") who runs a boarding house for ladies in trouble. This lady helps out Moll, and pays a woman to take away her baby once it's born (I didn't quite understand this part. Didn't they have adoption back then? Moll was quite worried the child would come to harm, but to her credit she follows up and makes sure it's OK with the new family). So Moll is now free to marry the banker, which she does. They live happily for a few years, until he loses all his money in speculation and then dies. Damn, Moll can't catch a break!

That's when Moll turns to crime. She commits a theft, and rather enjoys it, so she does it again. And again. She finds out her old friend "the governess" can help her fence the stolen goods. In fact the governess totally enables Moll's life of crime, and turns her onto this whole underworld of petty criminals. Moll becomes a very successful and legendary criminal. This section of the book goes on for a long while, and Defoe describes the details of her many crimes, which were especially enjoyable to read. My favorite was the time she stole a horse (she wasn't planning to, but the opportunity arose), but then she and the governess couldn't figure out how to fence a horse, so Moll had to return it.

Eventually Moll is caught, sent to Newgate prison, and is sentenced to death for theft (they didn't mess around in those days!). But she repents to a preacher who is sympathetic, and he helps get her sentence commuted to banishment to Virginia (along with the help of a bribe). She also discovers her not-really-ex-husband Jemy in prison, himself caught for theft, but since there's not enough evidence to hang him, he plea bargains his sentence to exile to Virginia as well. So they go to Virginia together and start a plantation. Moll quite accidently finds her son and her brother/husband, who's grown old and senile. She is reconciled with her son, who gives her her inheritance from her own mother, the income from a working plantation. Moll and Jemy grow rich, are penitent, and finally move back to England when they're too old to work on the plantation. And they all live happily until death, having repented over their former lives. Or not. This is one of the interesting points about the book...Moll seems all penitent at the end, and repeatedly says she is. However, in the introduction, where Defoe claims he's merely "cleaning up" Moll's autobiographical text that she herself has written, he explains that he had to rewrite her manuscript because:

...the copy which came first to hand having been written in language more like one still in Newgate than one grown penitent and humble, as she afterwards pretends to be.

So call me crazy, but that sounds like Defoe is saying she's not really penitent. Which frankly is not surprising to me, and I suspect to the modern reader as well. In Defoe's day, it would be hard write a moral story about a whore and thief without the character being reformed at the end. But it's clear that Moll did what she did because she really had no choice. In those days, women were at the mercy of their husbands and their husband's fortunes. When luck ran out, as it did with Moll so many times, the women were thrust into dire circumstances. Moll proves herself quite clever and resourceful, and can thus deal with her setbacks. Which makes this story complex...is Defoe saying "Don't be like this woman, she's a thief and whore and a bad person"? Or is he merely seeming to say that on the surface, while he's really sympathizing with Moll, who is merely being resourceful in the face of unbounded adversity? Moll certainly is a devious trickster (don't trust her with your wallet) but she also seems to have a good heart. But does she really repent? I dunno, she seemed to enjoy much of it a little too much.

All three of the narrators in the three Defoe novels I just read (Robinson Crusoe, the unnamed narrator of "Plague Year", and Moll Flanders) all have a number of similar traits. They're all quite intelligent, they're all quite resourceful, and they all have to be resourceful to stave off death! They're all phenomenal observers of what's going on around them. And they're all basically loners; Robinson Crusoe obviously so, but also the "Plague Year" narrator, who lives alone as the plague hits and seems to have no friends, and Moll, who is continually abandoned by men, and who leaves all her children. Her only true friend in the book is the governess. It's only at the end when she's reunited with Jemy that she has a stable marriage.

Anyway, this is one of those books I was sad to see end. I really liked Moll, and I heartily recommend this novel. Defoe is great. Of all the authors I've read so far in the course of this blog, he's the one I'd most like to sit down and get drunk with...he seems like the type of guy a scientist could relate to: an observer at heart, with an eye for detail. The three books I've read are his best known works...If anyone has any other Defoe books they'd recommend, I'd love to hear about them.

Tuesday, September 2, 2008

Book #20 - A Journal of the Plague Year (Daniel Defoe)

In 1918 my grandfather was a young, newly-married pharmacy student when he caught the Spanish Flu. Fortunately (especially for me) he did not die, but he was ill for a long time and had to go to his wife's parent's farm to recover. He eventually did, but he had a perpetual hacking cough afterwards. As he recovered, he began to work on the farm, and he and his wife ended up staying there all their lives; my grandfather thus became a farmer, taking the farm over after his parents-in-law died. Flash forward thirty years to 1948...he's working on the farm one day and cuts himself very badly on a piece of farm equipment. The wound gets infected and he goes to the doctor. The doctor gives him a new medicine that has recently come out...penicillin. My grandfather takes the antibiotic, and not only does his wound quickly get better, but within two days the hacking cough he'd had for the last thirty years went away and never returned.

We are so used to modern medicine today that we take it for granted. Bacterial infections which would have been fatal before World War II, or at least caused lifelong chronic complaints like my grandfather's cough, are now just nuisances that can be easily cured with a dose of antibiotics. Until the emergence of AIDS, death from infectious diseases became like an odd curiosity, only imaginable in some third world backwater. But with the emergence of new viral infections, like AIDS and SARS and (maybe) bird flu, and the increasing resistance of many bacterial strains to even the strongest antibiotics available, we are again entering an era where the threat of death or disability from infectious disease looms large over our lives. And there's no better reminder of what life can be like in the middle of a raging epidemic than Daniel Defoe's "A Journal of the Plague Year", which describes the 1665 epidemic of bubonic plague in London.

This was a book I found grimly fascinating and rather odd. I say odd because the book is a fictional account of one London resident's observations of the great London plague of 1665. It's fiction, but it's hard to call it a novel. It seems incredibly historically accurate, and the writing style is very journalistic. If we didn't know anything about the author, we would immediately assume it really was a journal written in 1665 by a plague survivor. Defoe is really good...it takes a lot of talent to pull it off and make this narrative seem so authentic. Defoe himself did live in London during 1665, but he was only five years old. I've read that the nameless narrator (we only learn that his initials are H.F.) may be based on Defoe's uncle, Henry Foe, and many of the details may be from his uncle's journals. I don't know if that's true or not, but Defoe has clearly done a lot of research to get all his details...no one could make this stuff up.

The book has no plot. It loosely follows the course of the plague, from a few isolated cases in early 1665, to the epidemic's climax in September/October of 1665, when thousands were dying every week. The book rambles...the narrator makes an observation, and then follows up with it for a paragraph, or a few pages, then goes on to some other observation. Many pages later he may come back to the same observation and add more to it. If the subject matter wasn't so morbidly intriguing, this rambling style might put the reader off. But the narrator's observations of the plague, his descriptions of the behavior of the victims and the survivors, and his religious and scientific (such as they are) musings keep the reader hooked. The narrator describes the city's attempts to stop the epidemic, which involve, among other things, locking up any house where someone falls victim to the plague. Anyone living there aside from the victim was also locked in the house, and a guard was posted outside. This may have helped prevent the disease from spreading as rapidly as it might have, but it also condemned anyone trapped inside to an almost certain death. In this way whole families were wiped out. The narrator describes how the rich and well-to-do fled London as soon as the plague appeared. Poorer people tried to flee London once the epidemic spread, but by that time neighboring towns were turning folks away, often with force. Quacks selling patent medicines to prevent the plague made lots of money deceiving people, before they themselves succumbed to the disease. People fled to the church for salvation, where clergymen died in large numbers due to their exposure to so many people. Interestingly, the narrator tells how when the Church of England clergy died, preachers from dissenting churches were often the only ones who were left to take their place, and they did so to much acclaim...the plague doing more for religious tolerance than anything previously attempted. Of course, once the plague passed, the persecution of dissenting sects began anew. Carts came through the streets on a daily basis, the drivers calling out "Bring out your dead" (yes, just like in Monty Python). The dead bodies were stacked in the cart and taken to the churchyard where they were dumped for mass burials in large pits. When people went to the store, they would not hand money directly to the shopkeepers, but instead would dump their change in a bucket of vinegar on the counter, which was thought to disinfect the money.

The book goes on and on with observations similar to these, all equally though-provoking. And that's the whole book. We learn almost nothing of the narrator...we know he's a saddler, and that his brother and his family have left the city for safety, and that he himself never catches the plague, but that's it. However, he does venture his opinions on things he sees (for example, he's very much against the locking up of houses of people who have the plague), so he's not just an impartial reporter of the events. But the main character of this book is really the city of London and its beleaguered population.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing in the book is the response of people to the plague as it reaches its terrible climax and then begins to wane. When the plague is at its height, and thousands are dying each week, the narrator makes the despair eerily palpable. Everyone has given up hope and just assumes that they'll all be dead soon. And then, the plague starts to abate. Not only do the number of deaths begin to decline, but more people who come down with the disease begin to recover completely; the disease has become less virulent. When people realize this is happening they are overwhelmed with joy, and lose all the caution they had...people talk to one another in the streets again, and touch one another, and do business. Many people die as a result, for the epidemic is not over, but people just don't care...the glimmer of hope has caused them to give in to the universal need for human contact. Humanity returns.

A final historical note, and one which the narrator of the book mentions: The summer after the great plague of London came the great fire of London, and most of the city burned down. What was perhaps not so appreciated then was that this was probably a blessing, in that large parts of London were effectively sterilized, and rid of the rats and their fleas which spread the plague. When the city was rebuilt, under the auspices of Sir Christopher Wren, the streets were made wider, and a better sewage system was put in. Ironically London's great fire may have helped prevent future epidemics and their miseries. This book serves as a vivid reminder of what we're missing, and what we may yet experience again some day.