Tuesday, October 23, 2012

The Age of Innocence (Edith Wharton)

Holy Mother of Pearl! Let me just say this was a really great book. And that's not just the Limoncello talking. Yes, I had a bottle in the freezer left over from when I visited Italy last year, and I polished it off tonight. I still can't figure out if I like the stuff...it has a nice flavor, but it's a bit too sweet for my tastes, I think. Edith Wharton, though, is none too sweet. I read "Ethan Frome" in high school and "The House of Mirth" in college and there was nothing at all sweet about those books. Man were they depressing...hellish glimpses of people coming to horrible ends after getting fucked over in relationships. So why would a guy like me, without a girlfriend at the moment, have the balls to read more Edith Wharton? Did I think it was going to motivate me to run out there and get hitched up? Nah, actually I had the book on my shelf, and it intrigued me, and even though it's not on the list for this blog I decided to take a break and read it. And wow, am I glad I did. This book maybe my new favorite of all the ones I've blogged about so far, right up there with "Silas Marner" and "Anna Karenina". It was entertaining, it was intellectually stimulating, and it made me weep. I mean seriously, this book hit me over the head with an emotional frying pan at the end and had me totally bawling, and that's not just the Limoncello talking. But then, we'd already established that last point.

"The Age of Innocence" takes place in Old New York. I'm guessing 1870s/1880s, when high society folks lead rather trivial lives of socializing according to very defined rules. Everyone knows what the rules are, but no one really talks about them. Spouses don't really communicate on a deep level. Everything is formal. Newland Archer is a rich young lawyer who grows up in this world and gets engaged to his sweetheart, May Welland. May is gorgeous, and Archer loves her. All seems good. Then May's cousin, Countess Ellen Olenska, comes to town. Ellen grew up in New York, and was a childhood friend of Newland's, but she married a rich Polish count and moved to Europe. The Polish dude turned out to be a total asshole and cheated on her, so she ran off with his secretary, and then came back to the US. Everyone in New York high society is freaked out because she'd been living in Europe, and everyone knows those European people have mysterious ways that can't be trusted, plus why would any woman leave her husband? Her family, and Newland, work to get her integrated back into New York society but she's always regarded with suspicion. She's too free and unconventional, and everyone hates that. Except Newland. No, poor Newland suffers the fate of realizing how confining his pitiful life really is, and he totally falls for Ellen. Especially as he slowly finds out his wife doesn't have much of an interior life. He longs for more. He tells Ellen he loves her, but they both agree they shouldn't upset other people with such trivial feelings such as love, so Newland goes ahead with his engagement and he and May get married. Oh fuck, people, is it EVER a good idea to get married when you're in love with someone else? No, but Newland and Ellen were trapped by their society so they decided to try to ignore their feelings.

Newland and May are married and settle down to their life in New York. Memories of Ellen fade from Newland's mind until he runs into her again on a vacation out of town. Ellen promises not to go back to Europe while they're still in love, but once again she says they must not act upon their feelings. But after awhile, when Ellen moves back into New York City to take care of her grandmother who has had a stroke, she meets Newland again and they decide to consummate their affair. FINALLY!! But before that can happen Newland learns that Ellen is moving back to Europe, and May announces that they are to have a farewell dinner for her cousin in their house. Newland is freaked out by all this, and not at all happy, but what can he do? So they have this huge dinner party, and May makes him sit next to Ellen, and it's then he gets this totally paranoid feeling that everyone at the party thinks he and Ellen had an affair, and that this send-off is the best thing for him since it gets this adulterous bitch out of town so that Newland can focus on his wife who has always been true and faithful. Or is this really merely paranoia? After the guests leave, and Newland says goodbye to Ellen for what he presumes to be forever, May comes in to the study and tells him she's pregnant. She also says she told Ellen this a few days ago, right before Ellen suddenly decided to go to Europe. Ohh, snap! This woman, May, who Newland regarded as innocent and unobservant has apparently engineered the removal of Ellen from the scene.

Flash forward twenty years. Newland and May had several children. Newland's life with May was content, and his longings for Ellen slowly receded, and when May dies of pneumonia he is genuinely sad. He travels to Europe with his oldest son, who's grown up in a new generation where things aren't so stifling socially. These modern kids, they hang loose! In Paris his son suddenly says "Hey let's go visit our cousin Countess Olenska. You really loved her, didn't you Dad?" Newland's mind reels..."WTF did you just say, son?" His son tells him that his mother (May) said to him on her deathbed that their father would take care of him and his siblings, that he was a good man because he gave up what he wanted most so as to keep his marriage vows and stay with his family. This is where I started bawling. Newland had felt so alone in his suffering over Ellen. I know what unrequited love feels like and he suffered his over the course of years with a wife he didn't communicate with at a deep level. And yet, all long she knew how much he had loved Ellen, and she knew what a sacrifice it was for him to give her up. He hadn't been alone, but yet he never knew it. He had regarded his wife as someone who was oblivious to life and yet she was way more clued in than he ever imagined.

Anyway, his son drags him to see Countess Olenska. She's single and living in Paris. Newland reflects that he's only 57 years old, and that times have changed and no one would think twice if he took up with Ellen. They get to her apartment and Newland sends his son up, telling him he needs a moment. Newland sits on a bench, reflects that he prefers to remember the Countess as she was, that she was more real to him in his memories, and so he gets up and walks home without going up to see her. The End. Wow, not a sad end, but not a happy one either. Much like life sometimes.

I pondered the title "The Age of Innocence". Is Wharton referring to the days before World War I, when society had these rigid rules of conduct? Is she referring to youth...to the young Newland Archer who thought he could have it all, who didn't really know WTF he was doing emotionally? I don't know. After all, what do I know about literature, as I'm a biochemist tipsy on Limoncello? But I do know I loved this book. So sad, so wistful, and Wharton nails the psychology of her characters. If you're looking for a great book to read, try this one.

Sunday, October 7, 2012

Book #54 - Uncle Tom's Cabin (Harriet Beecher Stowe)

I found this gem of a quote in the news yesterday:

"The institution of slavery that the black race has long believed to be an abomination upon its people may actually have been a blessing in disguise. The blacks who could endure those conditions and circumstances would someday be rewarded with citizenship in the greatest nation ever established upon the face of the Earth."

-- Arkansas state Rep. Jon Hubbard (R), quoted by the Arkansas Times

I seriously doubt that Jon Hubbard ever read "Uncle Tom's Cabin".

There have been several books I've read for this blog project so far that have dealt with slavery. Frederick Douglass' and Booker T. Washington's autobiographies, along with "Pudd'nhead Wilson" and "Beloved" all dealt with the issue in different ways, but none were so blunt and direct and powerful as Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin"...well, OK, maybe "Beloved" but that was written years after slavery ended.

Harriet Beecher Stowe was an abolitionist and the wife of a seminary professor. In 1850, congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, which outlawed people in the north assisting runaway slaves. In fact, if a runaway slave was caught in the north they had to be returned. This fanned the flames of northern outrage against the institution of slavery and inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write "Uncle Tom's Cabin". Published in serial form, the book became a HUGE bestseller, and one source I read said it was the top-selling book of the 19th century. The book drew widespread praise in the north, and condemnation in the south. After the Civil War broke out about ten years later, Harriett Beecher Stowe was invited to a White House dinner, where Abraham Lincoln allegedly said, upon meeting her, "So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war".

The book is an interesting read to say the least. First of all, it's almost impossible not to think about its historical significance when reading it. Nowadays we are accustomed to thinking of slaves as real human beings who lived and suffered and died under terrible circumstances. In particular, I can remember as a kid when "Roots" was on television, and it was a huge event. And books by modern authors like Toni Morrisson have brought to life the experience of living under slavery. But "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was a first...it brought slave characters to life, and depicted in great detail the inhumanity of slavery to an audience that oftentimes did not regard slaves as quite being human. In particular, the author was a mother who had lost a young child, so she was very good at depicting the horrors of children being separated from their mothers, and of families being broken up by the slave traders. It's hard to imagine how shocking this book must have seemed to readers in the 1850s. IT gave them a new way to look upon their world.

To a modern reader, even to one slightly tipsy from a delicious snifter of brandy (the most prevalent form of alcohol consumed in the book...which is weird because I kind of doubt that would have been the go-to drink of southern plantation overseers. But then I would also bet that Harriett Beecher Stowe did not often encounter alcohol up close and personal, so maybe she was just improvising here. But I digress...), the book can seem dated. For one thing, it's very preachy. HBS leaves no doubt as to her feelings on slavery, and she is not afraid to hit you over the head with it every few pages. Characters go into long speeches debating slavery, which almost turns sections of the book into sermons rather than conversations between characters in a story. And in the final chapter, after the story formally ends, HBS just comes right out and speaks directly to the audience about the horrors of slavery, and claims that all the characters and their lives are based on true incidents that she has known or has heard about.

Also the book is VERY religious. Uncle Tom is a devout Christian, as are several other characters, and you are hit over the head with the idea that Christ helps them make it through their terrible struggles, and that they will be happy in the afterlife because they have lived good Christian lives. I don't think I've read this religious a book in a very long time, maybe not since I read the Old Testament. There's no doubt that the author was a very devout Christian, and she does not let you forget it. However, she is not preaching Christianity at the audience like she is preaching abolition...instead, you can tell that she assumes her audience is Christian and she has no need to preach about that...instead she is hammering home the idea that since you (the reader) are a Christian, then you cannot possibly be supportive of slavery, because look how awful it is and look what good Christians some slaves are.

And finally the book seems dated because it's pretty damn melodramatic. The author really knows how to pull at the heartstrings! Beautiful angelic children die, and teach their parents the joy of accepting Christ as they pass away! Hardworking, scrupulously honest, devout Christian slaves are tortured and beaten to death! Beautiful young women slaves who are devout Christians are sold to gross, sleazy men who will use them for...well, you know what they will use them for! Slaves escape to the north, barely eluding their pursuers at every turn, saved only by devout Quakers who have their backs! And these same Quakers, when the evil slave pursuers are injured, nurse them back to health where they will learn to accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior and live good lives from now on! Oh, the humanity! And yet, one has to admit that yes it's all melodramatic, but the author does melodrama really, really well. The book is a page turner, and is only slowed down here and there for some serious anti-slavery preaching and diatribes.

Not only is the novel melodramatic, but the characters often seem like stock figures and not real human beings. The character of Uncle Tom is one example. Uncle Tom is a good man...portrayed as being completely honest, very hard-working, intelligent, loving to all children (both black and white), and an incredibly devout Christian who sings Methodist songs, reads the Bible, and teaches his fellow slaves about Christianity and the Bible. He pretty much has no flaws. Through his owners financial woes and death, he ends up on the plantation of the evil sadist Simon Legree, where he is flogged for not wanting to flog his fellow slaves, and where he is finally beaten to death for refusing to divulge the whereabouts of two fellow slaves who have run away. He's too good to be true. Which brings up an aside which has me puzzled after reading this novel...in popular culture, at least nowadays, an "Uncle Tom" refers to a black man who is obsessively subservient to white people, or to authority figures. Now the Uncle Tom in the novel definitely respects the authority of his owners, and is an extremely hard worker, but he refuses to beat his fellow slaves when ordered, and he refuses to rat on his fellow slaves who have run away. I see him as a character almost like Ghandi, or Martin Luther King...a man who practices non-violent, religious-based civil disobedience when asked to do something which would compromise his religious principles. He goes along with his owners most of the time because he's a slave and doesn't know anything else and is a hard-working man, but his greater allegiance is to his God and Christ and he will not compromise those for any man, even if the man owns him, has a whip, and is not afraid to use it. For this reason, Simon Legree hates Uncle Tom, because he knows that he can never terrorize him like the other slaves, and will never be able to break him, because his Faith keeps him strong. Stock character or not, you have to admire the man. He's definitely no Uncle Tom.

Most of the other characters seem like stock figures too...in particular, the angelic little white girl Eva, who Tom meets when he saves her from drowning when she falls off a riverboat, and who then convinces her father to buy Tom. Eva has no faults and as a six year old can see the abject horror of slavery and is beloved by everyone in the household, both owners and slaves. Of course, she's too good for this world, and dies of tuberculosis. But she is unconcerned about her death because she believes in Christ and knows she's going to a better place.

Anyway, despite the melodrama and the anti-slavery diatribes and the overbearing Christianity and the stock characters I think this book is well worth reading. For one thing it's worth reading for its historical value, because if we forget the huge horrific inhuman role that slavery has played in the history of this country then we're condemned to have to listen to idiotic quotes like the one at the start of this post. Racial injustice and prejudice are still something we deal with in this country, and reading this book helps give a historical perspective on how far we've come (hey, we have a black president!) and how far we still have to go. It's amazing that all this happened not so very long ago really. It's part of our history and that history still continues. But the book is also worth reading because even if it's often a contrived melodrama with stock characters, it's a damn good story. Oops, I shouldn't say "damn"...

Sunday, September 9, 2012

Book #53 - The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Victor Hugo)

After marching across the Persian Empire with Xenophon, I decided I wanted to take it easy. All that marching got my throat dry and my feet tired and my mind weary, so I figured it was time to sip on a real nice glass of rye whiskey (the Van Winkle 13-year old Family Reserve always will do in a pinch, or any other time for that matter) and kick back with a light-hearted fairy tale of a novel. At least that's what I thought Victor Hugo's "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" would be like...you know, a kind of Disney-esque gothic romp featuring an ugly but loveable hunchback who gets the girl in the end because she learns to see past his hideous visage. Well, Jesus H. Christ in a chicken basket was I ever off the mark. This book is way more Brothers Grimm than Disney. It deals with serious fucking issues, like the persecution of women, and the depravity and corruption of the church, and in the end almost everybody dies a horrible and tragic death. A fascinating book, but man what a downer. I definitely needed an extra glass of whiskey at the end of this one.

Victor Hugo actually named this book "Notre Dame de Paris", since the great Gothic cathedral is where most of the action takes place. In fact it's almost like the Cathedral and the city of Paris are the central characters in the book. Hugo goes to great lengths to describe and praise the architecture of the cathedral, and to describe what Paris was like in the 1400s, when the novel takes place. It's clear Hugo loves Paris and its great Gothic cathedral. The book was written at a time when Gothic architecture was out of style, and looked upon as primitive and archaic, and Hugo's novel was a love note to Gothic Paris, and proved instrumental in getting the attitudes of Parisians to change in regards to their architectural heritage. It was after this novel that the cathedral was renovated and preserved from a state of descent into disrepair.

The three main characters in the novel, not counting the cathedral and the city, are a priest, a hunchback, and a gypsy girl. Of course there are other characters too, like a soldier, an impoverished poet, and even the King of France. In fact, one of the revolutionary things about this novel was that the characters spanned the gamut of Parisian society, from the lowest street people up to the very top of the pecking order with the King. The priest, Claude Frollo, is the archdeacon of Notre Dame. His parents died of the plague, and his only family is a younger brother, who he raised after their parents died, and Quasimodo the hunchback, who he adopted after he was left abandoned on the church steps. Claude loved these two, and raised them as family, but the brother turned out to be a drunken bum, and Quasimodo is, well, a grotesquely ugly and deaf hunchback (he's deaf because his job is to ring the church bells, and they're really, really loud). Claude is incredibly smart, and has studied everything there is to study (he was clearly an overachiever as a young man). So at some point he continues his search for knowledge by studying alchemy and the occult. This makes the parishioners think he's a sorcerer, and he becomes isolated from them. That's clearly not good for his mental health, since his brother and Quasimodo don't make such a great social circle.

Then Esmerelda, a stunningly beautiful and free-spirited gypsy girl, comes to town. She hangs out in the town squares, making money by dancing and having her trained goat perform tricks. The crowd is convinced the goat's tricks are actually witchcraft, but they don't care because they're so entertaining. But then Claude Frollo sees her, and all is lost. He becomes hopelessly besotted and completely obsessed. So Quasimodo tries to go kidnap her and bring her to the priest. But Quasimodo is fended off by some royal soldiers as he attempts to snatch Esmerelda up off the street, and Quasimodo is sentenced to be beaten in public and chained up for public humiliation. As he is chained after his beating he cries out for water, but none of the good citizens of Paris come to help him, since he's a scary, hideously ugly hunchback and not only are they all pretty much afraid to approach him, but they're also getting pleasure out of seeing him suffer. So as he cries for water, only Esmerelda approaches and she gives him a drink from a pitcher. He cries the only tear he has ever shed, and he is instantly and eternally grateful. His heart has changed from this gesture of compassion.

But in the meantime Esmerelda has become hopelessly besotted and completely obsessed herself...with the soldier that rescued her from the attempted abduction. This is the second love in the novel, along with Claude's love for Esmerelda, that is blind and obsessive and leads to tragic consequences. And actually the two other loves in the novel, Quasimodo's love for Esmerelda, and Esmerelda's mother's love for her daughter, all don't turn out so hotly either. Hmm, I wonder if someone had broken up with Hugo before he wrote this. Anyway, Claude learns of Esmerelda's infatuation with the soldier, and doesn't like it one bit...so he formulates a sneaky plan. He befriends the soldier, gets him drunk, and learns that the solider is going to see Esmerelda that evening in a hotel room. The soldier is clearly a cad who just wants to bang the hell out of the poor but gorgeous gypsy girl before dumping her and moving on. Claude convinces the soldier (who doesn't know Claude is a priest) to let him hide in the room and watch while he porks the young gypsy. The solder, apparently thinking that this will lend some extra kinky energy to the evening, readily agrees. So as the priest hides, the soldier leads Esmerelda up to the room. He then slowly proceeds to get her to relax so he can make his move. She's nervous and shy, because she's an innocent virgin, but she's so over-the-top crazy for the soldier that she soon decides to let him have his way. And at that moment, as the solider climbs on top of Esmerelda, Claude leaps out from his hiding place and stabs a knife right through the soldier's back. Ouch! The priest runs off and the landlady downstairs hears the soldier's scream and calls the cops, who come and take Esmerelda away. She is put on trial for murder of the soldier (never mind that there's no evidence, or that the soldier actually recovered from his wound and rejoined his unit). The judges are convinced she's a sorceress (come on, a gypsy with a dancing goat? That's gotta be witchcraft...there's no other explanation) and she is found guilty and sentenced to death. So in a public ceremony watched by a huge crowd, she is hauled in front of the cathedral as archdeacon Claude Frollo comes out. He is supposed to lead her in an apology to God, and then she will be dragged across the square to the gallows. Claude whispers in her ear that he still could save her if she just lets him have his way with her. She is disgusted and refuses, so the priest says the benediction and then turns away and lets her go to her fate. Then, right before she's lead off to the gallows, Quasimodo swings down on a rope like some crazy hunchback Spiderman, grabs Esmerelda and disappears into the church with her, yelling "Sanctuary!!!". The crowd goes wild with excitement, because what they just saw was so damn cool. Anyway, Esmerelda is now safe inside the cathedral, because it's sacred space that's beyond the law. But of course, now she can never come out. Oh, and I know you're concerned, so I'll just say that Quasimodo had the presence of mind to save the goat too.

This is some powerful shit, theme-wise. Hugo is dealing with issues like the corruptness and power of the clergy in French society, sexual repression in the clergy and its unfortunate results, and the mistreatment of women. God forbid you're a beautiful woman who innocently shows off her sexuality and performs tricks with a dancing, counting goat. You will clearly be sentenced to death under some pretense because, well, you're stepping out of line there, even though it's titillating...or perhaps because it's titillating. Interestingly, Hugo describes how when Esmerelda is being dragged in front of the church and then to the gallows her dress barely covers her and is shockingly revealing. Yep, let's show off the gorgeous girl's body before we kill her as a witch...only seems fair.

Anyway, now that she's stuck in the cathedral, the priest goes to her and tries to rape her, but is fended off by Quasimodo. The priest is like a father to Quasimodo, because he raised him, and Quasimodo has loved and revered the priest, but his attempted rape against Esmerelda turns the tables for him, and Quasimodo realizes what an evil scumbag the priest has become. And of course Quasimodo now loves Esmerelda, since she's the only person who has shown him any compassion. Esmerelda appreciates the hunchback, who helps her be comfortable in the cathedral, but she's too frightened by his appearance to ever really totally appreciate him as a man and fellow human.

Anyway, the priest is pissed because he can't rape who he wants to rape when he wants to rape her. So now he wants to get Esmerelda out of the church so he can either (1) rape her somewhere that Quasimodo won't find them and then beat the living crap out of him, or (2) have her captured and executed because if he can't have her, well then no one can. Yeah, nice guy this priest. Anyway, the priest hunts around for an idea to get Esmerelda out of the cathedral, and finally approves an attack on the church by a mob of poor people who want to loot the place and set her free. The indefatigable Quasimodo defends the cathedral the mob, at least for awhile, and kills lots and lots of the attackers, including the priest's drunken brother. But finally, through some confused signals, the king (who is shown to be a buffoon) sends in the army to both kill everyone in the mob, and seize Esmerelda from inside the church so she can be executed, sanctuary be damned. But then Esmerelda escapes, just in time!! Oops, but then she gets caught, but not before she is reunited with her birth mother, who long ago gave her up for dead when gypsies carried her off. But dammit, as the soldiers seize Esmerelda they also kill her mother, so the happiness of reunion that they've each waited for all their lives lasts only about five minutes. And that was the happiest part of the ending of the novel. For Esmerelda is hung in the public square, and as the priest watches her die from the tower of Notre Dame, he laughs. Quasimodo is so pissed at this that he throws the priest off the tower to his death. Then Quasimodo goes and lays down with Esmerelda's body inside a paupers tomb, where he stays until he too dies of starvation. The end.

Yep, Hugo has written a life-affirming Disney-esque tale, full of magic and gypsies and a loveable hunchback and an innocent goat performing cute tricks. Oh, and attempted rape, crazy obsessive stalking, and death...all due to a priest's sexual repression. Man, that's still a hot topic, even today. This book seemed much more modern than I thought it would be. Way more depressing, and way more modern. Which made me really appreciate and enjoy this book...once I got over the depressing and shocking ending. Man, I think I need another whiskey just thinking about it...

Friday, August 10, 2012

Anabasis (Xenophon)

Meanwhile, back in the Persian Empire...

Yes, I have deviated from my top 105 books yet again, motivated in part by my recent reading of "The Histories" by Herodotus. If you'll recall from my recent post on that book, which I KNOW you've read, Herodotus describes the invasion of Greece by the Persians, under the kings Darius and Xerxes, from about 493-479 BC. But what happened to the Persian Empire after the invasions of Greece failed? Well, in 404 BC Xerxes great grandson Artaxerxes II was crowned leader of the Persian Empire, much to the dismay of his brother Cyrus the Younger. Cyrus was the Satrap (ruler) of Lydia, a kingdom in what is now western Turkey, but Cyrus was not happy with that. He wanted to be leader of the whole damn empire, and so he formulated a plan...and that's where the story in "Anabasis" opens.

"Anabasis", or "The March Up Country", is a memoir by the Xenophon, written in the third person. Xenophon was a wealthy aristocratic young Greek...what we might refer to as a "country gentleman". He was clearly ferociously intelligent and charismatic, and was a friend of Socrates. When Cyrus the Younger hires an army of 10,000 Greek mercenaries to allegedly fight enemies in Ionia (the Greek region on the west coast of Asia Minor) Xenophon decides to go along and check out the action. Little does he or the army know, but Cyrus has other plans for them. The army marches east, but doesn't fight anyone. Hmm, that's odd. They keep marching east. "WTF?" asks the army. "Where the Sam Hill are we going?" Soon it becomes clear...Cyrus is taking the army east to attack his brother and claim the throne of Persia for himself. The army rebels...it's one thing to fight for booty in Ionia, but to go into the heart of the Persian Empire and overthrow the king...now that's way too much for them. Heated discussion ensues, but Clearchus, a Spartan, convinces the Greek mercenaries to continue with the expedition. After all, imagine how generous Cyrus will be to them if he becomes leader of the Empire. The booze, the broads..totally worth it. So the army marches on, deeper into the Persian Empire.

Meanwhile, Artaxerxes II hears of this, and assembles an army to go meet his brother's forces. Their armies clash at Cunaxa. The Greek mercenaries rout their Persian foes, but Cyrus and his bodyguatds spy Artaxerxes II and charge in to kill him. A javelin is thrown, piercing Cyrus through the eye, and he dies. Uh oh. It is not immediately apparent to the Greeks what has happened, because they won their part of the battle, but when they learn about Cyrus's death it dawns upon them how totally fucked they are. Now they're deep in Persian territory, Cyrus is dead, and they have no food, friends, or supplies...so all they can do is run for their lives. They start to retreat, but are pursued by the Persian army. Artaxerxes II would like to see them all dead, to teach a lesson to any would-be revolutionists. The general of the Persian army, Tissaphernes, has a problem, though. The 10,000 Greek soldiers are to large a force to directly attack, and they need a lot of food, since 10,000 mouths are a lot to feed. So Tissaphernes comes up with a plan. He tells the Greeks he will make peace with them and lead them out of Persia, and the generals of the Greek army should come to his tent and have a feast to celebrate and make plans for the assisted withdrawal. So the leaders of the Greeks all go to Tissaphernes' tent, where he has them seized and beheaded. If General Ackbar had been there he would have shouted "It's a trap!", but alas that did not come to pass. Now the Greeks are so totally fucked it's not even funny. They could have split up and been picked off one by one, but somehow they pull their shit together and elect new leaders from the within ranks...and Xenophon is chosen to lead the whole army. Which he does.

What follows is an incredible tale of adventure. I don't want to go into a lot of details, because I highly recommend this book and you should read about what happens yourself. But imagine Xenophon's problem...you have to lead 10,000 men on a very long trek home through enemy territory. And we're talking 10,000 men! Xenophon's army is basically a wandering plague of locusts, stripping the countryside bare of food, firewood, and other provisions (including, probably, women) and no doubt leaving behind a trail of garbage and, well, human waste. They pass through some barbarian lands, where the barbarians run into the surrounding mountains and throw rocks down upon the army. I mean, what else could they do...you can't fight a 10,00 man army, but you don't want them to stick around and destroy your crops and villages and then move on. Xenophon tries to keep the army in line, and not have them suck up everything in their wake, but what can he do...there's 10,000 hungry young men to feed!

As the army marches along it's one damn thing after another. Attacks! Treachery! Snow and bitter cold! The story reminds me a bit of the Shackleton story...adventure upon adventure, with each escape miraculous, often involving cunning, strategy, or brilliant oratory by Xenophon. Someone should seriously turn this book into a comic book or graphic novel. It's unbelievable, and yet it all really happened. Of course, in Shackelton's ill-fated Antarctic expedition not a single man was lost. In Xenophon's case, only about 6,000 of the original 10,000 made it out alive. Still, that's not bad, given the obstacles they faced. Even once they make it "safely" back to Greek territory they are still in danger. The Greek cities don't want them around, again because they're like locusts. People try to hire them, but there's always a catch. Finally, a Spartan hires them and the army, now being gainfully employed once again, sets off to fight. It is here that Xenophon takes his leave.

This is a much more personal book than Herodotus. You can imagine yourself with Xenophon and his men, battling their way from WAY behind enemy lines. If you ever saw the movie "The Warriors" you'll know what I mean. And if not, just read the damn book. It's a good one.

Friday, July 27, 2012

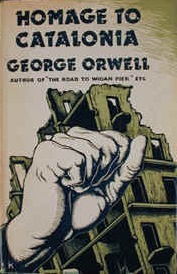

Homage to Catalonia (George Orwell)

I was reading in the news today that Spain is having some kind of financial crisis or something. Greece, Italy, Spain...come on Europe, get your act together. Although actually I don't follow the financial news all that thoroughly, which combined with my hobbies of reading, blogging, and drinking fine American whiskies probably accounts for why I'm not going to be able to retire for another 94 years. Nonetheless, even I know that something is amiss in Spain, and it sounds like no good will come of it, whatever it is. Bonds, maybe...something to do with bonds. Or banks, or maybe the Euro. Whatever. But as bad as it might be at the moment, and we'll just assume that it really is dangerous, it can't be anything like the Spain that George Orwell describes in "Homage to Catalonia", his memoir of the Spanish Civil War. I mean, as he describes it that place was seriously fucked up.

Now I know, you're thinking "WTF is he writing about this book for, because it's not on his list? Maybe he's so addled by old age at this point that he doesn't even remember he has a list, or something like that". Well, I may indeed be addled, but as I've said before in this blog, I will occasionally read a book not on my master list just because I want to. In this case, this book has been sitting on my shelf for about 25 years (I kid you not). I was stirred into reading it after watching "Hemingway and Gellhorn", a made-for-HBO movie about Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn, a war correspondent who eventually became Hemingway's wife and later went on to become Hemingway's ex-wife. It was an amazingly shoddy movie, especially given the cast and given that it was HBO, but regardless it stirred my interest in the Spanish Civil War and so I decided to read Orwell's book since I really did buy it about 25 years ago and figured it was now or never for reading it. Especially since my brain apparently is becoming addled with age.

The Spanish Civil War was unlike any war today. For one thing, artists, writers, filmmakers, and other creatives of all caliber seemed to flock to the thing and pick up rifles and fight. Boy, that would never happen now. I don't see Seal or J.K. Rowling picking up some body armor and rushing off to Afghanistan. In fact, if anything, they'd stay as far the fuck away from that place as they could, or from any other war zone for that matter. But something stirred the creatives of the world to flock to Spain in the 1930s and pick up arms against Franco and the Fascists. I guess everyone could agree that the Fascists were bad, but then can't we all agree that the Taliban is bad? Whatever. But as we all might suspect, it turns out that artists and poets make pretty crappy fighters because eventually Franco and the fascists won.

Orwell, however, did not know the eventual winner of the war when the events in the book take place, and he didn't even know when he wrote the book. That in itself is poignant enough, but what really makes this book memorable is his descriptions of life at the front, and life in Barcelona during a period of street fighting. Orwell headed to Spain and signed up to fight with a regiment made up of members of a political party called P.O.U.M. No, that's not the Pomegranate Juice...P.O.U.M. was the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, or the Worker's Party of Marxist Unification. There was a whole alphabet soup of political parties in revolutionary Spain, and while Orwell goes into great detail about the different parties, this was one part of the book that was hard to follow, and frankly a bit dry. It seemed like P.O.U.M. were communists associated with Trotsky somehow, as opposed to other communist parties which were not, and possibly associated with Anarchists, but also maybe not. I don't know. The take-home message was that there were a lot of parties all struggling against one another and trying to position themselves, while maybe they all would have done better if they just focused on fighting Franco and the Fascists together. Which they did, when they weren't undermining and fighting one another.

Orwell talks about when he arrived in Spain there was truly a revolutionary atmosphere. Workers had seized all the buildings and communist, revolutionary, and anarchist flags were everywhere. Everyone called each other "comrade". No one was allowed to tip, and even in the army everyone was assumed to be equal (which would seem to make it hard to fight a war if everyone could question their commanders). In short, a revolutionary worker's paradise. Unfortunately of course, it didn't last.

Orwell joined a P.O.U.M. militia unit and was sent to the front to fight the fascists. He describes what it was like to fight at the front in very evocative details. He talks about the sights and smells of living in the trenches (to sum up: it's all bad) and he talks about the ubiquitous rats and lice that plague everyone (memo to self: avoid lice. Also avoid trench warfare). These parts made the most interesting parts of the book. Orwell alternates between (1) telling his story and describing what his life in wartime Spain was like, and (2) describing in detail the political machinations between the various parties and factions. In other words the chapters alternated between gripping and not so gripping.

After spending time at the front, Orwell returns on leave to Barcelona, where he notices the revolutionary fervor that was so rampant when he first arrived is completely gone. The workers have been beaten down and are back in their places. But more importantly the P.O.U.M. party that he has been a member of is suddenly outlawed, which is not good for him. They have been accused of being Stalinist sympathizers, or maybe Trotsky sympathizers, or maybe fascist sympathizers. As a result, the government militia, or maybe its the communists, have turned against them. But wait, are the communists and the government working together...or do they hate each other? Ah, who the fuck knows. Why couldn't these fricking Spaniards have a regular civil war like we had in the good old U. S. of A...you know, the North against the South, Yankees vs. Johnny Reb, freedom vs. slavery...with just two sides, making it easy to figure out who's who and what's what? That would have made things a lot simpler in Spain, and who knows, maybe the good guys would have won then. But now I'm getting off track.

And speaking of which, I just need to say that I'm drinking a Margarita in order to salute my Spanish heritage, which consists of having ordered burritos in taquerias all over California. Those things are Spanish, right? Along with the Spanish flu and Spanish fly...

So where was I? Oh yeah, so P.O.U.M. gets outlawed and street fighting breaks out all over Barcelona. Of course in all the revolutionary confusion it's not clear who is street fighting against whom. That's the problem with street fighting, as opposed to two armies facing one another across no man's land while hunkered down in lice-filled trenches. Nonetheless, Orwell survives the fighting and confusion in Barcelona, and survives the P.O.U.M. purge, and makes it back to the front lines of the war, where in short order he is shot in the neck. He is seriously injured but he survives (as evidenced by the fact that he wrote this book). His doctors tell him that "a man who is hit through the neck and survives is the luckiest creature alive", but Orwell wonders if it would even be luckier not to have been hit at all. So Orwell lingers in Spain for a short time longer, but then leaves the country in order not to be killed in the continuing P.O.U.M. crackdown. The End.

One can think of the Spanish Civil War as a prelude to World War II, with communism and democracy fighting against the fascists. Yet the fascists won the Spanish Civil War, and his experiences lead George Orwell to write "1984". I suppose all ideological moments end in frustration and apathy, and this one was no exception. Still, one can't help but wonder what would have happened if Seal had picked up arms and joined Orwell on the front lines of this conflict. Perhaps history would have turned out completely different and this whole financial crisis thing would have been averted. Or not.

Saturday, July 7, 2012

Book #52 - The Histories (Herodotus)

These

kids today I swear...they throw around terms like "old school" when

referring to things that are from 2007. Well screw that..."The

Histories" by Herodotus was written sometime around 450-420 BC. Now

THAT'S frickin' old school. In fact, Herodotus is often referred to as

"The Father of History" since his is the first work of western history

that we have, and one that he extensively researched and systematically

arranged. Now, by research I mean he traveled all around the ancient

world, talked to everyone he could corner in a bar, and wrote down their

stories. Which leads me to wonder...what did he write stuff down on?

Paper? Papyrus? Did he use a pen? Did he carry all his notes around

with him in a backpack? Because he was so old school that he didn't

have a MacBook, or even a Commodore 64 running WordPerfect, on which to

take notes. In fact, this was before people made notebooks, or index

cards. So the practical aspects of writing a history like this in 450

BC are troubling to ponder. Unless he just had one helluva freaking

amazing memory. But who knows...so let's just drink our whiskey and get

on with it.

Here are presented the results of the enquiry carried out by Herodotus of Halicarnassus. The purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and non-Greeks...

How

poignant is that: "To prevent the traces of human events from being

erased by time"? That's depressing when you think about it, especially

when it comes to our own lives. All the traces of our pain and

heartache and joys and thrills and loves erased by time. Crap, maybe I

need to drink some more whiskey to help that process along. Hold

on...ahhh, better. Anyway, Herodotus did a good job at meeting his

objective because he is the sole source for much of the history and

incidents he recounts. He did indeed prevent the memory of these things

from being erased by time. Good going, dude!

As

one starts reading "The Histories" it quickly becomes clear that

Herodotus's work is not what would today be called a history book. For

one thing, Herodotus is much more anecdotal. While the book does

recount the origins and history of the conflict between the Greeks and

Persians, it's not a dry recounting of a chronology. Instead the book

is laden with stories about individuals and events, many of which are

fun and interesting to read, and some of which are probably not true

(like the story of large ants that dig for gold). But they're fun to

read anyway, so what the hell. The second big trait of Herodotus's work

is that he often goes off on long tangents that really digress from the

narrative of the historic events. The most notable of these is in

Chapter 2, where he goes on and on about the customs, culture, and

religion of the people of Egypt, whom the Persian Empire invaded before

they turned their eyes to Greece. These digressions are fun, and

contain valuable anthropological and ethnographic information, but in

our modern era of book editors and ADD drugs they are quite unexpected.

Herodotus

chronicles the rise of the Persian Empire under its first great leader,

Cyrus the Great. One of Cyrus's early conquests was of the ancient

kingdom of Lydia, whose leader was Croesus. Croesus ruled from 560-546

BC, and was a very happy and wealthy man (hence the phrase, still in

use, "as rich as Croesus"). I mean, this dude was so loaded with dough

that Herodotus tells us he let his guests leave the palace with as much

gold as they could carry, and Croesus didn't sweat that one bit.

Croesus conquers some Greek cities in Ionia, and then thinks that maybe

he should invade Persia. So like any good king back 2500 years ago, he

first consults an oracle (no, not the software company) and asks whether

he should invade Persia. The oracle tells him that if he invades

Persia he will destroy a great empire. So Croesus gets all amped up,

does a double fist pump, and proceeds to invade Persia. Of course it

turns out that the great empire he destroys is his own, as he loses his

kingdom to Cyrus and becomes his prisoner. (Lesson: always think

through carefully what an oracle tells you). This story seems to be a

parable of one of the great truisms of life, that good fortune is not

immutable, and that happiness and good fortune and wealth can all

disappear in an instant, depending on both chance and bad choices. This

theme of course is also mirrored in the defeat of the rich Persian

empire at the hands of the poor Greeks.

Cyrus

goes on to conquer other lands, including Babylon. Then, when he is

killed in battle, his son Cambyses takes over as head of the Persian

Empire. Cambyses invades Egypt, and it is here that Herodotus goes into

the great diversion I've already mentioned, going on for pages and

pages about the people and culture of Egypt. It's interesting, and no

doubt of great importance to ethnographers and anthropologists and

Egyptologists, but some of the reading here was a bit dry for my

tastes. Nonetheless, the story picks up again when Cambyses conquers

Egypt, and then according to Herodotus goes insane. He tries to invade

Ethiopia with disastrous consequences, kills a sacred Egyptian bull,

kills his brother, and then marries and subsequently kills his sister.

Good times. Eventually some folks have had enough, and conspirators

kill Cambyses, and one of the conspirators, Darius, takes over as head

of the Empire.

Under

Darius, the Greeks living in Ionia revolt against Persian rule (500-494

BC). Darius clamps down hard on the situation, but then is so pissed

off at the Greek peoples that he decides to attack Athens and burn the

place to the ground as retribution. This lead to a showdown between the

Greek and Persian armies at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC)...about

20,000 Persians vs. 10,000 Athenians and their allies. The Greeks

charged and routed the Persians, resulting in 6400 Persian dead and only

192 Greeks dead. Go Athens...WOOOO!!! The Persians scampered away,

and Athens had saved all of Greece from Persian enslavement, paving the

way for classical Greek civilization to flourish and give us Plato,

Socrates, and all the other greats who formed the basis of western

civilization.

So

now everyone lived happily ever after in peace and harmony, right? Uh,

well, no. Turns out Darius was now even more pissed at the Greeks.

"#*$^$% Greek motherf#*$^#!! I'll #&$% kill those

@&*^$" he allegedly said, or something to that effect. So he

decides to put together a HUGE army and totally subjugate all of

Greece. Then he dies suddenly. Ah well, so all is forgotten then and

everyone lives happily ever after in peace and harmony, right? Um,

no...no such luck. His son, Xerxes, is even more of a hothead than his

old man, and decides to put his father's plan into action. So he takes

his HUGE army, which Herodotus claims has 2,641,210 men in it (which

seems like stretch to me, but whatever) and invades Greece. But two

things happen before the invasion which illuminate Xerxes's personality

for us. First, an old rich guy who's always been a loyal and trusted

supporter of Xerxes comes to him and says "Xerxes, dude, my five sons

are all in your army. Do you mind if the oldest one stays home with me

to look after the farm because I'm old and can't do it any more? The

other four sons will gladly fight and die for you". Xerxes tells him to

bring the eldest son to him, and when the father does Xerxes has the

son killed and his body chopped in half, and makes his entire army march

between the two halves of the son's body as they march out of Persia.

Lesson learned: don't fuck with Xerxes before he's had his morning

coffee...or afterwards either. Then, Xerxes has his engineers build a

bridge across the Hellespont, a narrow strait (located in modern day

Turkey) that separates Asia from Europe. So they build the bridge but

then a storm comes along and destroys the bridge before the army can

cross. This does not sit well with Xerxes, so after chopping the

engineers' heads off, he instructs his men to whip the waters of the

Hellespont and then throw chains in the water to symbolically tell the

Hellespont that it is his slave. Now in those days, when there were

Gods watching over everything, that was just not cool. But that's

Xerxes for you. No one messes with him, consequences be damned.

Anyway,

Xerxes has his fits and then his HUGE army invades Greece. It's only

the largest freaking army ever raised! Greece is doomed, right?!? And

to make matters worse, many Greek city states said "Fuck it" and decided

not to resist the Persians or help in the fight. This pretty much left

mostly Athens and Sparta to fight the Persians on their own.

Fortunately Sparta helped put together an alliance called the Hellenic

League, with Athens, Sparta, and some other city states all agreeing to

stop fighting one another and to pool their resources to fight the

Persians. They first met the Persian army head on at Thermopylae, a

narrow pass in the mountains where the Persian army had to pass through

to get to the rest of Greece. About 6,000 Greek defenders were there to

fight the several million Persians. The Greeks had the high ground in

defending the pass, so they had an almost impregnable position, but then

most of the Greeks freaked out and ran away, leaving only a small

ragtag defense lead by 300 Spartans and commanded by the Spartan king

Leonidas. Despite being hugely outnumbered, the Spartans and friends

held the enemy at bay for two days. But then on the third day, the

traitor Ephialtes told the Persians of a pass through the mountains by

which they could surround the Spartans. Goddamn those

traitors...they're always fucking things up!! This lead to the downfall

and defeat of the small Greek contingent. Herodotus describes how the

Greek defenders heroically fought with their swords, and then with their

hands and teeth, until they were finally killed to the last man. While

this battle was a terrible defeat for the Greeks, it assumed legendary

status almost immediately, and thus fired up the Greeks. This battle

sparked the legend of Spartan bravery, illustrated by a story Herodotus

tells of the Spartan Dieneces, who when informed that the Persian

archers were so numerous that their barrage of arrows would completely

block out the sun, said "So much the better...then we shall fight our

battle in the shade". Years later, a memorial would be put at

Thermopylae, with the famous epitaph "Oh stranger, go tell the Spartans

that here we lie, obedient to their decrees".

Meanwhile

the fighting raged elsewhere. The Greeks fought the Persians to a

partial victory at the naval battle of Artemisium, which happens at the

same time as the Battle of Thermopylae. With the Persian army

advancing, Athens was evacuated and was then plundered by the Persians.

The Greek fleet withdrew to Salamis, and when it heard that the

Acropolis in Athens had been sacked, many grew disheartened and decided

to leave and just go and settle elsewhere. But the Greek Themistocles

persuaded others to stay and fight, leading to the decisive naval battle

at Salamis. The Greeks were outnumbered by the Persians (so typical),

but since the battle was fought in a narrow strait, the large number of

Persian ships made it difficult for the Persians to maneuver. The

result was that the Persian fleet was decimated. Xerxes suddenly

freaked out, and worried the Greeks would destroy his bridge across the

Hellespont, stranding him and his army in Europe. So like a little girl

he turned and fled, leaving a smaller army under command of the general

Mardonius to see if they could make a last ditch effort against the

Greeks. But the Spartans and the Athenians and the rest of the Hellenic

League again pooled their efforts and defeated Mardonius at the Battles

of Plataea and Mycale (479 BC), which happened on the same day (there's

a lot of these same day battles in Herodotus...odd). The Greeks

decisively win both battles, and Mardonius is killed at Plataea, and the

Persian threat to Greece is thus ended! Yay!! So everyone lived

peacefully happily ever after, right? Well, no, of course not...a

generation later Athens and Sparta went to war with each other. But

that's not in Herodotus...that's chronicled in the work of

Thucydides...also on my "to be read" list. And that's a story for

another day.

The

work ends curiously. First, back in Persia Xerxes attempts to seduce

his brother's wife, and then his brother's daughter (the latter

successfully). This leads to the destruction of his brother's family.

Oops. Herodotus does not mention it in his book, but Xerxes is

eventually assassinated. Then the book ends with a flashback to an

anecdote about Cyrus the Great. An adviser suggested to Cyrus the

following (and I paraphrase): "We're a big and powerful country now and

can invade anyone we like. Let's conquer a rich, fertile country where

the living is easy, and then we can all move there instead of living in

this Gods-forsaken desert". Cyrus replies something like "Soft lands

breed soft men", and says it is better to stay in a harsh land and rule

rather than move to a soft and fertile land and be others' slaves. Why

does Herodotus end on this note? This may be a warning to the

Athenians, who had become very powerful after the Persian Wars and had

somewhat of an empire of their own. Or it may be a warning to the

effect that happiness never lasts, and that even when people are in a

good position they get restless and then want something better; but that

can lead to something less happy than what they had in the first place

and to their eventual downfall. And that's pretty much what happened to

Persia. Don't let it happen to you.

I

read part of this book when I was in college, but never finished it.

For anyone who has started this book and then put it down, I recommend

picking it back up and seeing it through.

Reading it now has been an awesome and rewarding

experience. Sometimes we leave things

uncompleted, through boredom or perhaps wanting something more

captivating and fast-moving, sleek and sexy, easy and fertile. But

often it turns out that we didn’t fully realize what we had in our hands

and tossed it casually aside because it was too much work, or took too

much effort. Tossing

something aside because the initial thrill has gone, or because we’re

distracted by something else that comes along, or because the going is not as easy as it was at first,

is a good way to miss out on the

best things in life. Sometimes it pays to stick it out in the harsh

lands and work on something that will stay with one for life, to

struggle against its being erased by the inevitable passing of time.

Thursday, February 23, 2012

Book #51 - An American Tragedy (Theodore Dreiser)

When you pick up a book called "An American Tragedy" you know pretty much know right away that it's gonna be a downer. And yep, no amount of whiskey could keep this book from totally harshing my mellow. You know from the start that it's going to end badly, and believe me this one does not disappoint. Towards the end it just gets grimmer and grimmer. Don't get me wrong...that's not all bad, and Dreiser does it well, but it's probably not a good book to read if you're feeling kinda low and looking for something to lift your spirits.

This is a huge book, divided into three sections, with each one ending in a death. In Book I we meet Clyde Griffiths, a young boy in Kansas City whose parents are street preachers. Clyde accompanies them on their preaching missions, and he hates it. When he's a teenager, as soon as he's old enough, he gets a job as a bellboy in a fancy downtown hotel, both so he can get away from the street preaching and his parents, but also because he's sick of his parents' poverty and he wants money. And the job totally opens his eyes..his fellow bellboys introduce him to the joyful world of nice clothes, booze, fine dining, and loose women (both dates and prostitutes). He starts dressing like a dandy and living the high life...well, as high as one can on a bellboy's salary in Kansas City. And the more money he makes, the more he wants, because then he can buy things for Hortense, the woman he lusts after. Hortense is hot, and she knows it, and she keeps stringing poor Clyde along, hinting she'll sleep with him if he just buys her one more thing. Finally it's a gorgeous coat she sees in a store window...she has to have it and Clyde desperately saves his money so he can buy it for her and maybe, just maybe, get laid. But then fate, or rather idiocy, intervenes. One of Clyde's bellboy pals "borrows" a fancy car from a rich man (unbeknownst to the owner) and convinces Clyde and their fellow bellboy buddies to grab some babes and head out to the country for a day. So they do so, but they stay out a bit too late, and then have to drive like crazy to get back to the hotel in time for their bellboy shift. The driver is reckless, and in his hurry he hits and kills a little girl in a downtown intersection. He doesn't stop, and drives away frantically, with Clyde and friends freaking out in the passenger seats, and finally the driver wrecks the car and the boys and girls all flee separately, at least those who are uninjured enough to do so. Because of this Clyde leaves town to escape the long arm of the law, and Book I ends. And this is Clyde's first mistake...he's not guilt of anything but fleeing, and if he'd just waited for the cops he would have been fine, since he wasn't driving, nor was he the one who "borrowed" the car. But poor Clyde is not the sharpest tool in the shed.

When Book II opens, Clyde has moved on to Chicago, where again he has found work as a bellboy. But as fate would have it, at this hotel he runs into a guest who turns out to be his rich uncle, Samuel Griffiths from Lycurgus, New York. Here I have to pause for a rambling aside...Dreiser gets my kudos for naming his fictional upstate New York town "Lycergus". This is a Greek name, and there are a couple of people named Lycergus in classical Greek history...one from Athens and one from Sparta. My point is that anyone familiar with upstate New York knows that many of the towns there are named for places or people from classical history...Rome, Utica, Troy, Ithaca...so I tip my hat to Dreiser for noticing this. I dunno, maybe that's a small irrelevant point but what the fuck, it's my goddamn blog and I can make any stupid observation that I damn well please. Hmm, OK, better stop and have a sip of whiskey here to get me back on track. Ahhhh...Blanton's Single Barrel, an excellent bourbon and because of the distinctive shape of its bottle known as the Holy Hand Grenade of bourbon. But I digress. Yet again. Dammit. Sorry, this bourbon is really great.

Where was I? Oh yeah, so Clyde meets his rich uncle and asks him for a job in the uncle's shirt collar factory in Lycergus. The uncle is impressed by Clyde's forthrightness, and also by the fact that he looks like his own son. Plus the uncle feels that Clyde's father got a raw deal when their parents died and he was cut out of the will. So the uncle tells Clyde to come to Lycergus and he'll give him a job. Clyde then makes his way to Lycergus and his uncle gives him a menial job in his factory. The uncle would like to treat Clyde better but his son Gilbert, Clyde's cousin, is very jealous of Clyde and does what he can to thwart him. So Clyde goes to work and is forgotten for awhile. But then his uncle remembers him, and feels bad that he's treating shabbily someone who, despite his being born in poverty, is after all still a family member. So he gives Clyde a raise and a promotion and has him supervising one of the groups of women in the factory who are involved in making collars. The only catch is that Clyde is told that management is strictly forbidden to get involved with any of the women working in the factory. Uh huh, you can see where this one's going. Soon Clyde finds himself attracted to a beautiful young woman who has come from the country to work in his group. He strikes up a conversation, they start meeting in secret, and soon enough Clyde has talked her into "going all the way". The woman comes from an even poorer family than Clyde's (her father was a poor farmer) but she's sweet and innocent and very loving. They both seem very much in love. Yay, love! But of course, they must keep their love secret from everyone, because Clyde risks his job should people find out.

Oh, but then shit starts to happen. Clyde's uncle is unsure how to deal with Clyde, since he's family but he's not a member of high society like the Lycergus Griffiths are. But he invites Clyde to dinner one night and there Clyde meets the young, rich, gorgeous socialite Sondra Finchley. Sondra starts asking Clyde to attend society events with her and her friends, mostly to get back at Gilbert who she's pissed off at. But slowly and surely Sondra starts liking Clyde more and more...despite his lower class upbringing Clyde is friendly and well-spoken and earnest, and handsome as well. In fact, folks mention how much he looks like Gilbert, but better looking, a fact which has to piss off Gilbert even more. Clyde quickly becomes totally infatuated with Sondra...not just because she's beautiful, but because she's rich as well. Clyde is enthralled by high society and wealth and money...in fact he's been enthralled and excited by money and what it can buy since the early chapters of the book...so naturally he's overcome by this opportunity to love and be loved by Sondra, and hopefully marry her.

But what about Roberta, you ask? Yep, there's the rub. Clyde quickly starts to forget about Roberta, and spends less and less time with her, much to her bewilderment. But less time doesn't mean no time, and they are still "doing it" (as the kids say today), and yep, Roberta gets pregnant. Dammit, I hate it when that happens! Clyde and Roberta freak out, and when the drugs they get from a pharmacist don't end the pregnancy, and when they can't find a doctor to perform an abortion (this was pre-Roe vs. Wade, after all) they are out of options. Roberta gets sad and angry and demands that Clyde marry her, telling him they can get divorced after the baby is born but that she wants the child to be legitimate. If he refuses to marry her, she says she'll tell everyone that Clyde is the father and cause a huge scandal. Clyde is terrified and angry, because the marriage or scandal will of course end his chances of living happily ever after in a wealth-filled future with Sondra. He has absolutely no desire to marry Roberta...he only wants Sondra now. But what can he do?

Whiskey time again...ahhhh, love this Blanton's.

Anyway, as Clyde is tortured by all this he chances upon an article in the newspaper about a young couple who drowned in a boating accident, and he then gets a brilliant idea...he can kill Roberta!! WOOO, brilliant...problem solved!!! He will take her out in a boat, make her fall overboard, and she will drown (she cannot swim). He'll make it look like he drowned too, and then he'll sneak back to town and all will be right again. Since no one knows of their involvement, and since he will make sure no one knows it's him on the boat with her, he will not be suspected. What an awesome plan!

Clyde decides to go for it...he tells Roberta they are going on a trip and that he'll marry her afterwards, and he takes her to a remote lake resort in the Adirondacks. He gets her out in a boat and then...and then...Dammit, he has a failure of nerve, and he realizes he can't do it. ARGH, so close!! But as he's looking down in the boat and beating himself up for being so weak-willed, Roberta sees he's upset (for reasons she obviously doesn't know) and stands up in the boat to come towards him to comfort him. He is angry at his own weakness, and angry at her for forcing him to marry her, and he unconsciously lashes out at her with a camera he is holding. She is hit in the face, she falls overboard, and she drowns. He could have saved her, but he just watches her as she drowns and then swims ashore. He thus ends up carrying through with his plan, even if by an accident, sort of. And so Book II ends.

But despite all his planning, his plan actually sucked. There were all sorts of angles he never thought through, because he's not all that smart, and within about a day the authorities realize this wasn't an accident and that Clyde Griffiths was the man in the boat who killed Roberta. Bummer. When the police catch up with Clyde a few days later, he's at another lake with Sondra and her society friends. That's the last he ever sees of them.

The rest of the novel is both rather dull and yet exciting at the same time. There is a very extended account of Clyde's trial, much of which rehashes the previous plot points. But it's also interesting to see these events through the point of view of the prosecution and the defense. Clyde of course never remotely has a chance...the jury hates him, especially after the prosecutor reads them Roberta's very poignant letters to Clyde. The prosecution even fakes some evidence just to seal Clyde's fate. Clyde is found guilty, and sentenced to die in the electric chair. And after an extended stay on death row, and despite much effort by his mother and a sympathetic preacher and his attorneys, he is finally executed, and thus Book III ends with yet another death. Heavy stuff. This last part of the novel, the descriptions of Clyde's agonizing stay on death row, and the portrayal of his mother (who turns out to be a surprisingly strong character, by the way), are very poignant and gripping. Memo to us all from Dreiser: avoid death row whenever possible.

So what's the point of all this? Dresier's story is based fairly closely on a real life crime...but why did he choose this material for such a huge novel? I think the key lies in the book's title. This is not just a tragedy, but an American one. And why is that? Because Clyde's motivation for all this is money...the urge to have money, the urge to have material things...nice clothes, nice cars, beautiful women. The urge to get ahead, to be a Horatio Alger story. But to get that position in high society, to get those riches, to move from lower class to upper class, he gets into a position where he's forced to kill someone. Her death means less to him than the dream of being with Sondra, the beautiful rich girl. Poor Clyde is driven to kill by the American dream. Someone with more wits, or a stronger sense of morality, may have been able to figure a way out of all this and achieve some happiness, but poor Clyde is too weak and naive and inexperienced to solve the problems he faces, and it ends up resulting in Roberta's death and his own execution. America tempts him, he takes the bait as best he can, and then America sends him to the electric chair. Oops. God Bless America.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)